By Paul J. Davies

Feb. 5, 2024

Brian Kelly is The Points Guy, a pioneer in the cottage industry that helps credit card users get the most out of airmiles and other rewards. He got into it when young out of a determination to always fly business class. His motivation? “I’m six-foot-seven!” he says.

Unfortunately for points obsessives like Kelly, rewards programs are under threat. This is a multibillion-dollar business in the US based on swipe fees that card users love, but opponents say hurts small shops and raises prices for consumers. Leading the campaign is Illinois Senator Dick Durbin, who got debit-card processing costs slashed over a decade ago, and last year introduced a Credit Card Competition Act.

The promised land for users of reward cards: A suite on a plane. Photographer: ROSLAN RAHMAN/AFP

None of this is straightforward. Forcing down the fees that fund such programs will hurt the profits of banks and airlines, but that doesn’t mean that Main Street will benefit. In fact, the biggest winners might be big spenders who are just bad at managing their money.

Credit-card rewards are a fascinating and peculiar phenomenon first launched in the early 1980s. At heart, they are a classic trick that lets people think they’re getting something for nothing while the real costs are hidden. Points are funded by so-called interchange fees, which are set by networks like Visa or Mastercard and are paid to the bank that issues your credit card out of the sticker price of the thing you are buying.

Rewards are very profitable for the businesses that run loyalty programs: They encourage customers to spend more and return to the same brands. In many ways, consumers are being led by the nose and yet everyone thinks they are getting a great deal. “They give huge value to consumers,” Kelly insists. “It takes a while to work it out, but people are getting better and better at using them.”

The difference between swipe fees and the cost of rewards is worth up to $20 billion each year to the two biggest US card issuers — American Express Co. and JPMorgan Chase & Co. — alone. That’s not pure profit: There are other costs and not all those fees come from reward card use. It’s big business for airlines, too. AmEx paid Delta Airlines Inc. $6.8 billion last year mostly for its SkyMiles, up from $5.5 billion the year before. Some of these miles are never used, but the majority help Delta fill seats often on less popular flights, or are spent on baggage allowances or cheap access to lounges. Competition is getting fiercer, and the cost of rewards programs has been growing faster than swipe-fee income at JPMorgan and AmEx for years, especially since 2021.

Swipe charges aren’t the only source of funding. Consumers are increasingly willing to pay for access to more sophisticated-sounding rewards. That’s why they sign up to the things like the $695-per-year AmEx Platinum card, for example, according to Andrew Davidson, chief insights officer at Mintel, a market research group.

The economics are clear when you think about it. Take cashback cards, held by about 70% of Americans, Davidson says. It ought to be fairly obvious that if your bank is giving you 2 cents back for every dollar you spend, it’s because they’re collecting more than that in swipe fees, which typically range from 1.5% to 3%.

And this is what bugs Senator Durbin and retailers who think interchange is too high. Merchants have little choice in how you pay and they have to swallow the cost if you use a card. So the argument goes, either that is baked into all prices and people using cash or debit cards are overpaying, or retailers are taking a hit on accepting credit cards.

However, capping interchange fees won’t necessarily mean lower prices; it might just boost retailers’ profits. “Make no mistake: this bill was specifically written to deliver a major payday for big retail and big grocery,” a bank lobby group wrote in a letter to Congress last September.

The evidence on what happens when swipe fees are cut is mixed. In Europe and the UK, regulators capped interchange fees at a fraction of 1% for both debit and credit cards in 2015. Card issuers lost a lot of revenue, but partly compensated by tweaking other processing fees. Ultimately, less than half the savings on interchange found their way to merchants and about two-thirds of that was passed on to consumers through lower prices, according to a 2020 study paid for by the European Commission.

In the US, the picture is murkier. Debit card swipe fees were capped in 2011 after Senator Durbin attached an amendment to the post-2008 Dodd-Frank legislation. That all but killed off debit rewards, but apparently didn’t help consumers at all. According to a 2014 study by the Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, two-thirds of merchants didn’t see a noticeable change in processing charges, while 25% saw swipe fees rise, especially on small-ticket items. That might have been because capping charges for high-cost payments encouraged banks to enforce a nominal minimum fee on small purchases. Even among merchants that saw costs fall, very few cut prices as a result.

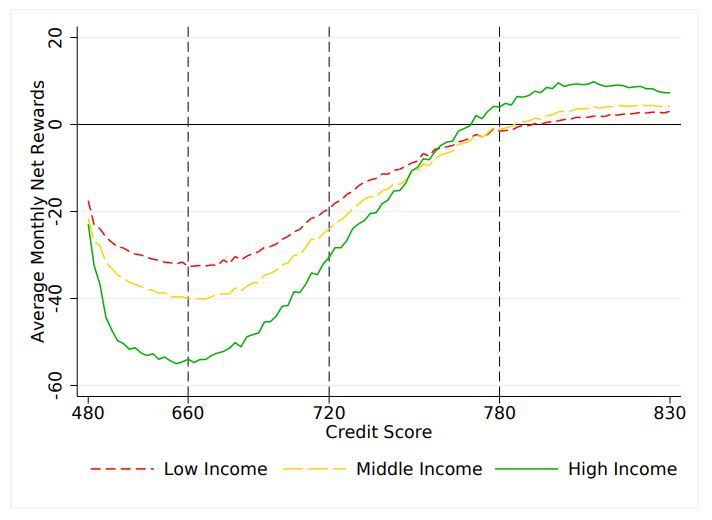

Dollar value of rewards earned after interest costs and swipe fees calculated for credit-card users of different FICO scores. Taken from the paper (hyperlink in the text above): “Who Pays For Your Rewards? Redistribution in the Credit Card Market"

Durbin’s main hope of helping ordinary consumers cope with rising costs of living is probably misguided. But I also think that rewards, no matter how much you love them, are probably a bad deal for most people. Those who get the best outcome are high-earners with strong credit scores who use their cards a lot but clear their balance every month and so pay minimal interest, according to analysis from two Fed economists and others published at the end of 2022. Those who get the worst deal are also high earners who spend a lot, but have low FICO scores, get fewer rewards as a result and also pay lots of interest on uncleared balances.

But probably most interesting of all, when accounting for the cost of rewards and bad debts against the income from swipe fees and interest earned, banks make more money on rewards cards across the credit spectrum than they do from plain old classic credit cards, according to the same study. In the end, it’s a bit like gambling: The house always wins.

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.