By Greg Ip

April 4, 2024

In The Wall Street Journal’s latest poll of swing states, 74% of respondents said inflation has moved in the wrong direction in the past year.

This assessment, which holds across all seven states, is startling, sobering—and simply not true. I’m not stating an opinion. This isn’t something on which reasonable people can disagree. If hard economic data count for anything, we can say unambiguously that inflation has moved in the right direction in the past year.

Inflation connected with food prices has decreased over the past year. PHOTO: GABBY JONES/BLOOMBERG NEWS

In the 12 months through February, inflation, according to the century-old consumer-price index, was 3.2%, compared with 6% a year earlier. Use a slightly different time horizon, or a slightly different measure (such as the index the Federal Reserve prefers) and you get similar results. Take out food and energy—or for that matter look only at food and energy—and inflation is still down.

Yes, some individuals faced higher inflation (someone who bought a house, for instance) but, for the average person, inflation went down.

Yet the average person thinks it went up.

When it comes to the economy, the vibes are at war with the facts, and the vibes are winning. This is obviously bad news for President Biden’s re-election hopes. He can’t exactly tell voters that they are wrong; he would be called out of touch. And it probably wouldn’t change anything. The vibes seem symptomatic of a broader pessimism disconnected from the data.

It’s tempting to chalk this up to a misunderstanding. Lower inflation means the level of prices is still rising, just more slowly than before. People sometimes conflate inflation with the level of prices and believe inflation is getting worse because the price level keeps going up (it rarely goes down).

A recently released Brookings Institution study by Harvard University economist Stefanie Stantcheva sheds light on exactly how people think and feel about inflation. It found that half of respondents defined inflation correctly, as rising prices. The other half defined it incorrectly, mentioning such things as “price gouging” or “overpriced everything.” So, some people might conflate high prices with high inflation. But enough to explain our survey results? Doubtful.

Moreover, the gap between vibes and facts goes well beyond inflation, strongly suggesting choice of words isn’t the explanation.

By 47% to 41%, more Journal poll respondents think their investments or retirement savings went in the wrong direction in the past year—a period in which the stock market roared to record highs, home values held steady or rose, and interest on savings went up.

The average customer retirement account at mutual fund giant Vanguard grew 19% last year. True, that didn’t make up for the 20% decline in 2022, especially after inflation. But it hardly qualifies as the wrong direction.

By more than 2-to-1 (56% to 25%), respondents said the economy had gotten worse rather than gotten better over the past two years. That is difficult to square with robust employment growth, unemployment near its lowest in half a century, or growth in gross domestic product, which actually accelerated last year.

As the saying goes, you can’t eat gross domestic product, or GDP. But what you eat is part of GDP and while people have said for several years that they are cutting back on groceries and eating out, the data show that Americans as a whole are spending more on groceries and restaurant meals, after adjusting for inflation, than in 2019.

To be sure, inflation and shortages were severe from 2021 through early 2023 and the improvement in the data since might not have been enough to erase those bad memories. Still, there is evidence people actually do notice things getting better around them. Surveys by the University of Michigan, for example, find consumer confidence has risen.

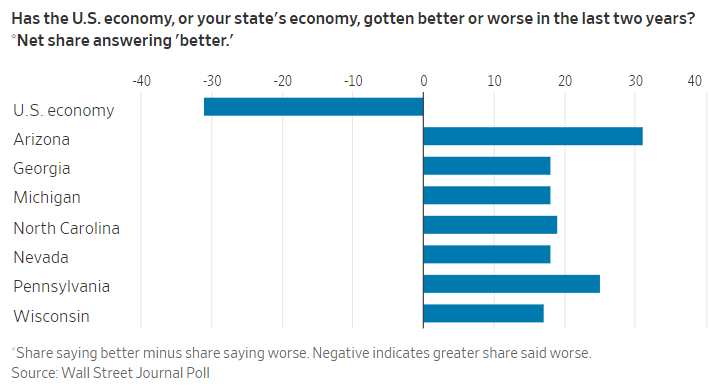

Moreover, while respondents rate the national economy as bad by a significant margin, they rate their own state’s economy as good by almost as much.

This is reminiscent of how voters tend to assign low marks to Congress but high marks to their own representatives. But the definition of a good Congress depends a lot on your politics, whereas the definition of a good economy ought to be somewhat objective. Everyone (except a few central bankers) wants lower unemployment. And swing states’ economies have largely tracked the nation’s.

All of this suggests that the bad vibes about inflation and the economy are interlaced with a deeper pessimism about the country—what I’ve previously called “referred pain.”

Stantcheva’s study shows that inflation evokes broader feelings of injustice. People tend to believe that prices rise faster than wages, that companies raise prices because they can but don’t raise wages because they don’t have to, and that the rich always do better with inflation. (Those things are true at times but not over long periods of time.)

Stantcheva told me that, while inflation clearly generates bad feelings, bad feelings about the country or the economy might make them more pessimistic about inflation. For instance, her study finds that, whereas economists associate lower unemployment with higher inflation, the public believes weak growth, high unemployment and high inflation all go together. As one survey respondent said: “To me, inflation is when the economy is more than just hurting. It’s when it’s too tough just to keep positive.”

So, if views on inflation are a function of broader pessimism, where does this pessimism come from?

One popular culprit is the media. A recent study of online news in Nature found that each negative word in a headline increases the click-through rate by 2.3%. This negative bias is nothing new: It was true of unemployment in the 1990s, and true of Covid-19 in 2020, according to research. (It’s even truer of social media—it’s called doomscrolling for a reason.) A recent Brookings analysis by Ben Harris and Aaron Sojourner suggested the negative bias of economic news has intensified in recent years.

But media negativity doesn’t necessarily cause public pessimism; it might simply be correlated. Stantcheva’s study finds that while people get information about inflation from a variety of media, they rely mostly on their own experience. People consume media that confirms their biases, and media—especially social media, with its finely tuned algorithms—tend to give consumers what they want.

The media and the public are negative for the same reason: They are worried about the country. It will take more than lower inflation to change that.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.