Yoshiaki Nohara

March 18, 2024

The Bank of Japan is widely expected to end its negative interest rate regime, the world’s last. The measure was adopted to encourage bank lending, spur demand and nurture inflation. Now the program’s mission is nearing an end as strong wage gains appear to bring the BOJ’s inflation goal into sight. The impact of the policy shift will vary across the economy and financial markets, benefiting some and creating challenges for others — or in some cases both.

iStock-531533905

1. What are negative interest rates?

They mean you pay interest to deposit your money at banks instead of receiving it. It’s a radical policymaking tool that central banks in Europe introduced in the 2010s to fight price erosion. The BOJ went negative in 2016, adding a fresh tool to its long battle against deflation, or declining prices. To be sure, the BOJ’s negative rate program was only applied to a small segment of deposits that private banks stash at the BOJ. Retail deposits weren’t subject to the policy. The aim was to encourage banks to put their funds to work via lending. The program was added to the BOJ’s aggressive buying of financial assets to flood the economy with money.

2. Have they worked?

The verdict on their effectiveness is mixed globally. In Japan’s case, they may have helped, along with the BOJ’s asset buying, to prevent deeper deflation in the economy. But ultimately it took supply shocks during the Covid-19 pandemic and the fallout from Russia’s war in Ukraine to spark the sharp gains in import costs of energy, materials and food that brought the nation’s inflation beyond the central bank’s 2% goal. The BOJ is the world’s last central bank that’s retained a negative rate policy. Its prolonged use cut into banks’ profitability and helped push down the value of the yen as other central banks raised interest rates, diminishing the relative allure of Japan’s currency. The weak yen has further fueled import cost gains, weighing on consumers as their paychecks failed to keep up with rising living costs.

3. Why is the BOJ poised to end the negative rate program now?

Japanese companies have agreed to large wage hikes, boosting expectations that bigger paychecks will make households more willing to spend money. That’s what the BOJ calls a virtuous cycle of rising prices accompanied by wage hikes. Last week, unions reported an initial tally of wage growth at the highest level in decades, fueling bets that the central bank will move early.

4. What will the end of the negative rate mean for the Japanese economy?

It will be a first step in the unwinding of monetary stimulus measures meant to put the economy on a self-sustaining growth path. For years, falling prices locked the economy in a downward cycle in which companies cut costs to be competitive even by sacrificing their profits. This downward spiral kept them from investing and raising wages, weighing on consumption and exerting a drag on prices. Now, Prime Minister Fumio Kishida hopes the opposite will take place, with investment, prices and wages all rising in tandem.

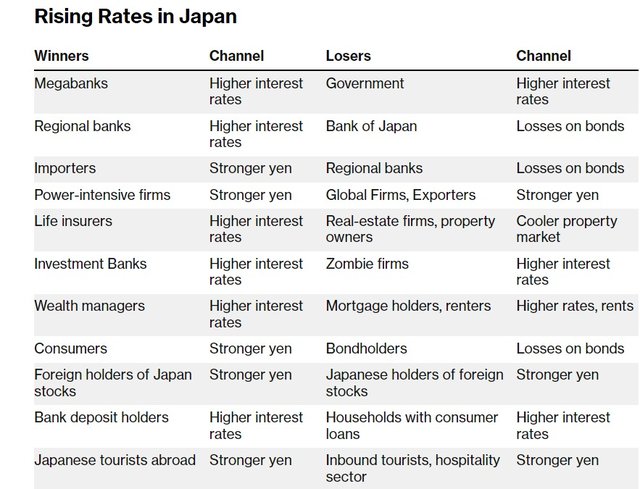

5. Who will win and lose?

The government and the BOJ will suffer in that higher interest rates will raise government debt servicing costs and cause paper losses on the central bank’s sovereign debt holdings as higher rates devalue them. Private banks will be able to make more profits from lending with higher interest rates while their bond holdings take a hit from rising long-term rates. Home buyers will see their mortgage rates rise, which might cool the real estate market. A stronger yen on the back of higher interest rates will cut import costs and help households with cheaper costs of imported food and energy. On the flipside, it will undermine the competitiveness and overseas earnings of exporters. For travelers going abroad, the strong yen will help them, while it will make it more expensive to visit Japan.

6. What’s next?

If the BOJ ends the negative rate with its first interest rate hike since 2007, the next question will be how high the BOJ will take its policy rate. BOJ Governor Kazuo Ueda has already indicated the bank’s overall monetary settings will stay accommodative for a while, meaning he won’t be conducting a series of rate hikes of the sort seen in the US and elsewhere in recent years. Weakness in consumption in Japan will warrant caution as the BOJ navigates its policy path in the new era.

© 2024 Bloomberg L.P.