By Jason Zweig

May 27, 2024

Thinking we know more than we do—overconfidence—may be our biggest handicap as investors. Knowing more than we realize, but not being able to use what we know, is another obstacle. It’s a mystery that’s finally getting some attention.

To be an investor, rather than a speculator, you must do deep and deliberate research before you buy an asset. As the late investor Charlie Munger liked to say, you must be “rational.”

iStock image

That doesn’t mean you must be as unfeeling as Spock on “Star Trek.” One of Warren Buffett’s most famous rules—“attempt to be fearful when others are greedy and to be greedy only when others are fearful”—is rooted in his ability to respond to emotion.

Spock wouldn’t be afraid of other people’s greed or greedy in the face of their fear; he would simply find their behavior inexplicable.

Buffett isn’t unemotional; he is inversely emotional. He takes other people’s feelings, turns them inside out and makes the resulting emotions his own.

In fact, you can’t be rational unless you’re also emotional.

People with damage to the amygdala, a brain region involved in processing fear, pursue “a disadvantageous course of action” when choosing between safer and riskier gambles, a study reported in 1999. The inability to feel fear leads them to chase gains with no regard for the consequences of losses.

Another region of the brain that’s been studied this way is the anterior insula, which relays awareness of bodily states such as your pulse rate, and processes reactions like anxiety and disgust. In an experiment in which people had to decide whether to keep buying a stock that rose up to at least 10 times its fundamental value before it crashed, those whose insula fired up more intensely sold out earlier and made more money.

Research published in 2016 found that professional traders who were more adept at estimating their own pulse tend to generate higher average daily profits over time and have longer careers.

That’s presumably because they were more closely attuned to their gut feelings; excitement may tell them to make a profitable trade, while fear may signal they should cut a loss before it deepens.

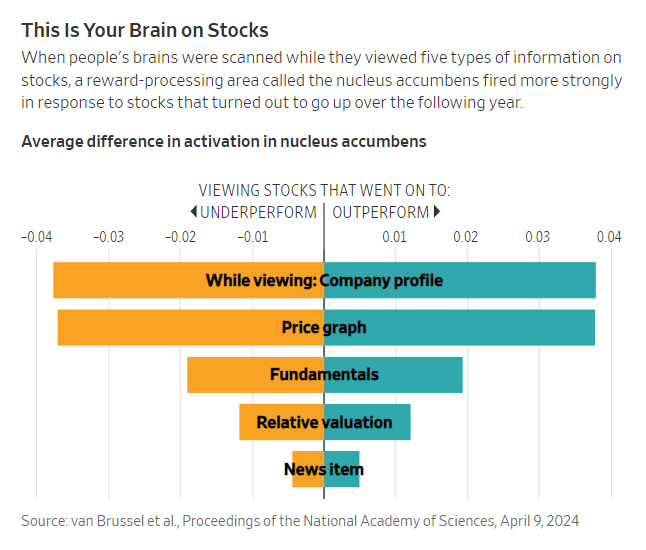

In the past few years, researchers have been investigating “neuroforecasting.” That’s the apparent ability of activity in the brain to forecast outcomes—even when people are unaware of it.

Neuroscientists have asked participants to predict which requests for microlending will raise the most money online, which ventures will receive the most crowdfunding, how popular video clips or songs will be, or whether a stock would go up or down.

Consistently, people’s conscious choices when confronted with these sorts of questions aren’t significantly better than chance. But the intensity of activation in their nucleus accumbens, an area of the brain that subconsciously processes anticipation of reward, turns out to be a good predictor of what people will collectively decide they like.

That’s right: A flicker of electrochemical activity in your brain—so faint that you may not sense it yourself—forecasts how people will react to something potentially rewarding.

In a study published last month, 36 Dutch professional investors attempted to pick winning and losing stocks while their brains were scanned in a functional MRI machine.

Among the stocks they evaluated: AT&T, Carrefour, Ralph Lauren, Sanofi and Teva Pharmaceutical.

For each stock, the investors viewed a basic profile, including industry sector and market capitalization; a price chart; data on sales and profitability; valuation relative to its peers; and a summary of recent news. The investors weren’t told the names of the stocks and said they didn’t recognize them.

The set of information the investors viewed dated back to various periods between 1999 and 2011. The investors were asked to say whether they thought each stock would outperform or underperform its sector in the 12 months after each measurement period.

Their conscious forecasts were no better than the flip of a coin. However, the researchers also measured the activation in the stock pickers’ nucleus accumbens. And that enabled the researchers to predict which stocks would outperform—with about 68% accuracy. The more intense the activation, the more likely that stock was to end up outperforming.

It’s as if these professional investors have useful knowledge without knowing it. Meanwhile, what they believe they do know—their conscious prediction—is pretty much worthless.

These results are “absolutely fascinating and counterintuitive,” says Brian Knutson, a professor of psychology and neuroscience at Stanford University. (He was a reviewer on the study but wasn’t otherwise involved.)

Many factors can influence investing decisions, including our past experience, our current mood and how much risk we want or need to take. That’s why individuals end up making widely divergent choices, even if their brains show similar initial responses to the same stimulus.

“The brain signal is more equal across a sample than the predictions are,” says Leo van Brussel, a neuroscientist at Erasmus University in Rotterdam who co-authored the new study. “So the brain signal is a better predictor across the population.”

You aren’t going to scurry into a brain scanner every time you’re about to make an investment, so how can you apply this research?

If you can detect, channel and shape your emotions, they can reinforce, rather than hinder, your ability to be rational.

I’ve learned that my feelings are good contrary indicators: When I’m fearful, I should instead be greedy, and when I’m greedy I should be fearful.

In the global financial crisis, I finally lost heart on March 6, 2009. But I knew my gut feelings well enough to listen to my fear—and to do the opposite. The stock market bottomed three days later, but I kept buying.

Brian Posner, an investor who had a distinguished career at Fidelity, Warburg Pincus and ClearBridge Investments, says his biggest scores were in turnarounds—companies on the brink of failure.

“In those situations, almost by definition, one is mostly or entirely alone in recognizing the potential,” he says. “Such investments are unnerving.” In those cases, he suggests, a good signal that you’re on the right track is “wanting to throw up.”

Turning other people’s emotions inside out has worked for Warren Buffett. Turning your own emotions inside out might work for you.

Write to Jason Zweig at intelligentinvestor@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.