By Greg Ip

Aug. 7, 2024

Unemployment is rising, stocks are falling and bond yields are well below short-term interest rates. These are all telltale signs of recession.

But a closer look suggests that while recession risk has risen, the U.S. isn’t in one now. The distinction is crucial because it means it isn’t too late to head off a downturn. It all depends on the Fed, and on the unpredictable moods of investors, consumers and employers.

Michael Nagle/Bloomberg News

Two events are driving the recession talk. The first is the stock-market selloff, which wasn’t triggered by news of the U.S. economy, but by the Bank of Japan’s decision Wednesday to tighten monetary policy.

The second event came days later when it was reported that the U.S. unemployment rate had jumped to 4.3% in July from 4.1% in June and 3.4% last year, triggering one popular rule of thumb that says the U.S. is in recession.

A recession isn’t a switch that is arbitrarily thrown on or off; it’s a process: a self-reinforcing cycle of weakening spending, employment and income, usually triggered by tight financial conditions such as high interest rates or a credit crunch, or a shock such as higher oil prices or, in 2020, a pandemic.

The increase in unemployment to date, according to a rule-of-thumb popularized by the economist Claudia Sahm, in the past has only occurred during recessions. However, this isn’t the definition of recession. It isn’t even a leading indicator of recession, like the yield curve. Rather, it correlates to the conditions that exist when the academic National Bureau of Economic Research has decided the U.S. is in recession. In a similar way, open umbrellas usually correlate to the weather service’s declaration of rain.

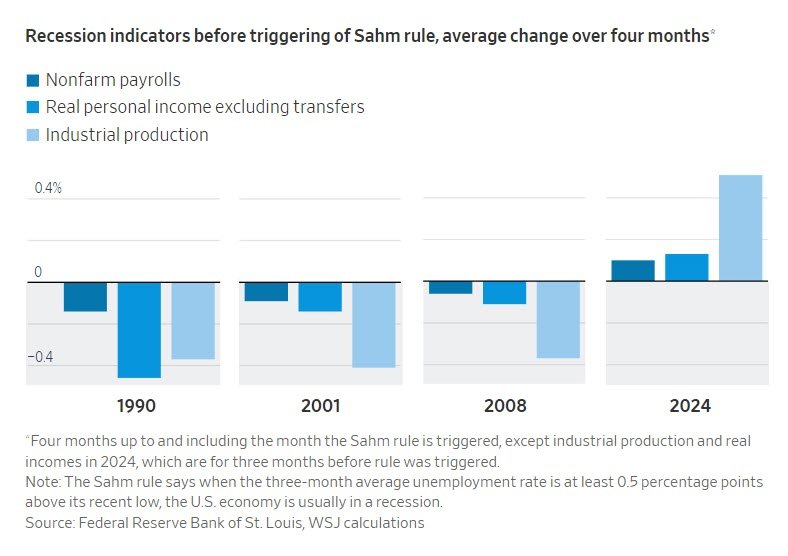

To decide if it’s raining, it’s better to stand outside than count umbrellas. Similarly, to determine whether recession has begun, better to look at the indicators the NBER uses than the Sahm rule. Three—payroll employment, industrial production and real (inflation-adjusted) incomes, minus government transfers—were all shrinking in the four months up to and including the month the Sahm rule was triggered, in 1990, 2001 and 2008. In all three, a recession had begun several months earlier.

In the four months through July, payrolls were growing, and in the three months through June, so were real incomes and industrial production. If a recession had already begun, it would be a very unusual one. (Sahm said last week she didn’t think a recession is imminent).

Two caveats: Data is often revised around recessions to be weaker than originally reported, and that could happen with this episode. Second, and more important, trajectory matters. The labor market has cooled, to date, enough to return it to a healthy balance. But if the forces behind that cooling are still at work, slow growth could become outright contraction.

One of those forces is the lagged behind effect of the Fed’s interest-rate increases. Will that be enough to push the U.S. further into recession? This is where the stock market comes in. The 8.4% decline in the S&P 500from its peak through Monday was slight, and partly undone by a rebound Tuesday. Recessions are almost always preceded by a stock slump, although not every stock slump has been followed by recession.

The reasons for a weaker market matter. Sometimes overleveraged market participants dump stocks for reasons having nothing to do with the economy. The Bank of Japan’s rate increase has caused a sharp rise in the yen, forcing a wave of selling by investors who had bet heavily on it staying low.

Whether such deleveraging leads to recession depends on whether the financial system also starts to crack, as it did in 2008. Of that, there’s so far little sign. Treasury bond yields were little changed Monday. They would fall sharply if panicked investors were flocking to safety.

It would be worrisome if stocks were forecasting weaker profits and sales ahead. Some prominent examples aside, such as McDonald’s, Intel and Delta Air Lines, companies aren’t saying that. Analysts reduced profit estimates last month by an average amount, according to FactSet.

Finally, falling stock prices can directly sap spending by reducing household wealth. They also have a psychological effect: businesses, which have already put the brakes on hiring, may be prompted to start laying off workers. That can feed back into stock prices and other financial conditions, in a self-reinforcing cycle.

The Fed can short-circuit such a cycle by cutting interest rates, which can revive demand for houses, cars, and other interest-sensitive purchases, bolster business investment and make stocks more attractive. Last Wednesday it signaled a willingness to do so in the fall and as a result bond yields have dropped, which should help the economy in short order.

However, bond yields are also below the shorter-term interest rates influenced by the Fed. Such an “inversion” of the yield curve has regularly preceded recessions.

In effect, the market is expecting that in response to recession risk the Fed will cut rates rapidly and deeply. Yet it has signaled it will only do so if inflation remains tame in the next few months. What if instead inflation is firm? That likely won’t last, given slowing wage gains, higher unemployment, and falling oil prices. But if the Fed doesn’t trust such a forecast, it may hold off, and accept the recessionary consequences.

Write to Greg Ip at greg.ip@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.