By Joe Pinsker, Elizaveta Galkina and Imani Moise

Sept. 9, 2024

If you want to know how Americans are doing, look in their wallets.

They have more money in the bank than they did in 2019, even after adjusting for inflation, and just slightly less credit-card debt relative to income. But they generally don’t feel better off financially than they did five years ago, before the turmoil of the pandemic, inflation and rising interest rates.

Heavier wallets have lightened the mood, though. We are getting more optimistic about the economy, according to the University of Michigan’s Surveys of Consumers. It doesn’t hurt that average 401(k) balances rose to about $127,000 in the second quarter of this year, from about $104,000 two years earlier, according to Fidelity.

Zooming in on the American wallet is a useful way to understand this moment of unease about the economy, and to think about how our own finances stack up, economists say. The mental anchor point many use to measure themselves against is 2019, because it was prepandemic and preinflation surge.

“It’s basically the most extreme comparison we could come up with, but also the most convenient one,” said Joanne Hsu, an economist at the University of Michigan who oversees its consumer sentiment survey.

A peek at what Americans have and owe reveals reasons for both optimism and angst.

Money

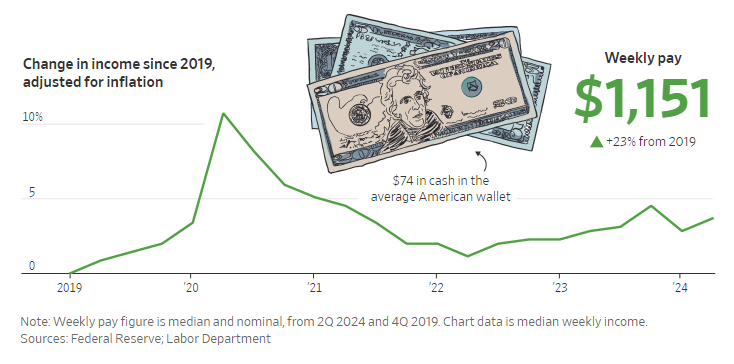

Americans make more money than they did at the end of 2019, even after adjusting for unusually high inflation since then.

Our emotions are harder to adjust for inflation. The pain of higher prices brought on whiplash or even nostalgia for the recent past.

This wage data is adjusted for inflation using the consumer-price index. It shows that real median earnings were about 3.5% higher in the second quarter of 2024 than they were at the beginning of 2019.

From 2020 to 2022, year-over-year pay growth was highest for the bottom 25% of earners, according to the Atlanta Fed.

Debit card

Americans carried an average of $74 in cash in their wallets and purses in 2023, up from $60 in 2019, according to the Fed.

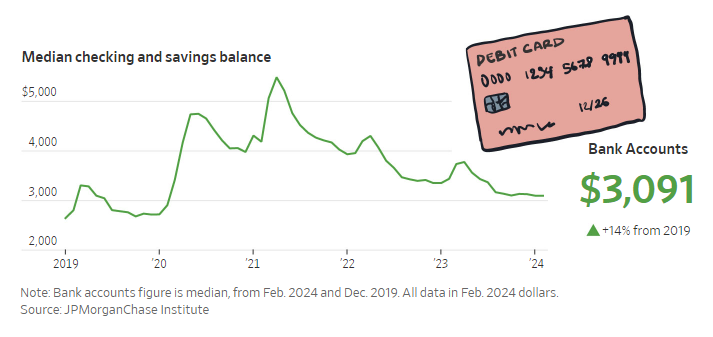

They also have more cash in the bank. Savings swelled in 2020 and 2021 because of Covid restrictions and government-stimulus payments. That cushion has largely been spent. “There is not money burning a hole in people’s pocket right now,” said Wendy Edelberg, an economist at the Brookings Institution.

Account balances fell from pandemic highs faster for lower earners. In February, the median balance for the bottom quarter of earners was $1,160, versus $8,143 for the top 25%, per JPMorganChase Institute.

Americans’ saving rate was down to 2.9% in July 2024, less than half what it was in late 2019, according to government data.

This reflects the confidence people have as a result of higher home prices, stock prices and income from bonds, said Torsten Slok, the chief economist at Apollo Global Management.

Credit cards

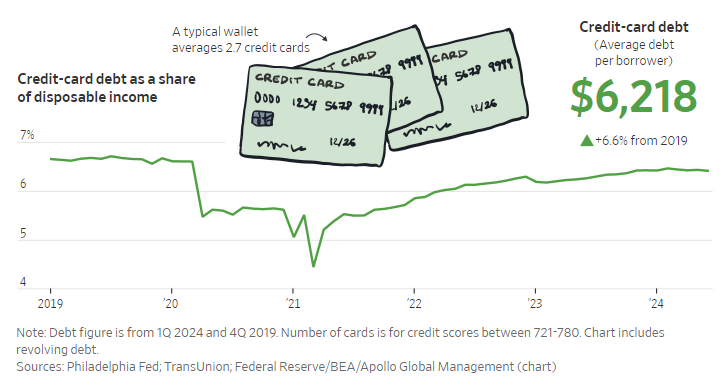

Americans have racked up more credit-card debt in the past few years, after paying down balances during the early part of the pandemic.

The average credit-card debt for those who carry a balance rose to $6,218 in the first quarter of this year, up from $5,834 at the end of 2019, according to TransUnion data. Card debt as a share of income is now just about even with what it was at the end of 2019, but higher interest rates—which have climbed to 23% from 17%—make it more expensive to carry the debt.

Slightly more than half of credit-card users now carry a balance from month to month, according to industry-research firm J.D. Power. Until last year, those who paid in full made up the slim majority. The median balance per card was $347 in the first quarter of this year.

Americans opened new credit cards at an unprecedented pace in the years following the pandemic, said Charlie Wise, head of global research at TransUnion. Most of the new cards went to first-time borrowers and those with less than pristine credit, he said.

There were about 590 million active cards in circulation in the first quarter of this year, 40 million more than in 2019. These new accounts helped drive total credit-card balances to an all-time high of $1.14 trillion in the second quarter of this year.

“More cards means more balances, and higher delinquencies,” Wise said.

Driver’s license

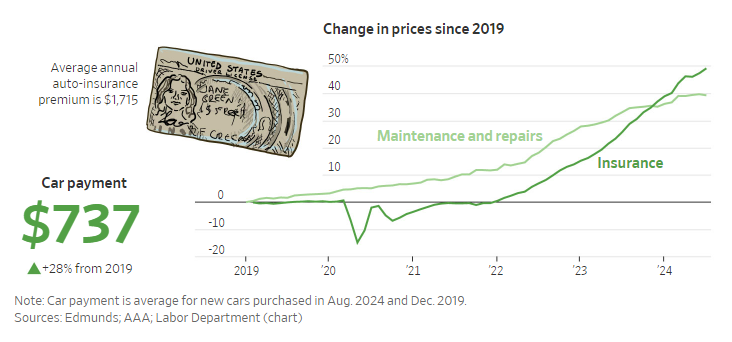

The price of a car and the cost of borrowing money to buy one have shot up since 2019. The average annual percentage rate on a loan for a new car was 7.1% in August, up from 5.4% at the end of 2019, according to Edmunds, an online car-shopping guide.

The costs of car ownership have similarly accelerated. Insuring and, God forbid, repairing a vehicle have become significantly more expensive lately. The price of gas is down from a spike in 2022, though still about 20% higher than at the end of 2019, based on Labor Department data.

Rising costs have inspired many drivers to get more years of life out of their cars. Partly as a result, America’s vehicles are getting older. Their average age stands at 12.6 years, up from 11.8 in 2019, according to S&P Global Mobility.

House keys

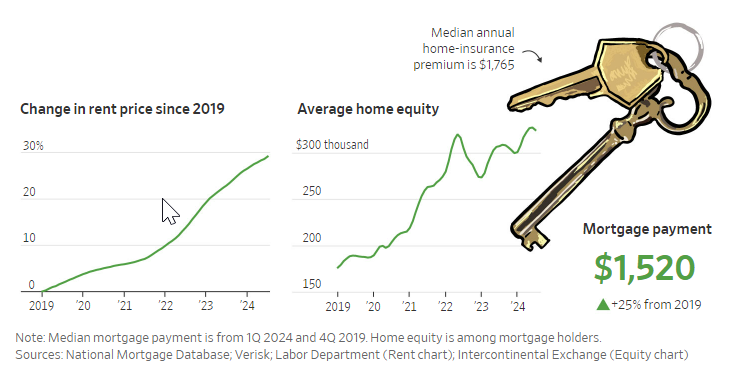

Housing is the biggest expense for most people, and for those who own a home, one of their most valuable assets. The past five years played out a lot differently depending on whether you had a landlord or a mortgage.

Homeowners got richer. A surge in prices raised the net worth of both longtime homeowners and millennials who lucked into great timing.

Rising rents, meanwhile, strained the budgets of tenants.

Though the median mortgage payment is $1,520, rising prices and interest rates have made buying a home far less affordable. The monthly payment on a purchase of a median-priced home in July with an average mortgage rate was $3,010, according to real-estate firm Redfin. In December 2019, it was $1,566.

The other costs of homeownership have also jumped, particularly the price of insurance. The median annual home-insurance premium was $1,765 in the first quarter, up from $1,164 in 2019, according to Verisk, an analytics firm.

But some relief might be coming to the housing market, as mortgage rates could drop as the Fed appears poised to cut interest rates. That could eventually give some homeowners a chance to refinance—and many renters a shot at buying a home.

Write to Joe Pinsker at joe.pinsker@wsj.com, Elizaveta Galkina at elizaveta.galkina@wsj.com and Imani Moise at imani.moise@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.