By Shawn Donnan and Claire Ballentine

Oct. 17, 2024

Some major milestones are becoming frustratingly unattainable for many families, helping to create economic pessimism that hangs over the election.

Illustration: Carolina Moscos

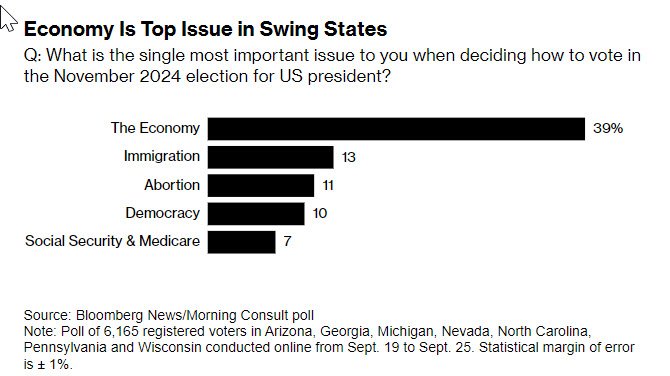

As US Election Day approaches, inflation is largely tamed and wage gains have lifted incomes. Yet the economy remains the most pressing issue in the presidential race for one big reason: Increasingly, for many Americans, the long-standing building blocks of middle-class life feel frustratingly unattainable.

The standard 20% down payment on a median-priced home now costs 83% of a year’s income for the typical family ready to buy a home, up from 65% on the eve of the 2016 election, according to Bloomberg calculations. Buying a new car takes almost two extra weeks of work for the median household compared to eight years ago. Child care then cost the same family about a quarter of its weekly income. Now it swallows up more than a third.

And while the cost of attending college has gone down as a share of income in recent years, a median household can expect to pay 75% of its annual income for a private college and more than third for a public in-state university. That is up significantly from when many of today’s parents went to college themselves — and, in turn, can make the price tag look unnerving.1

That represents a repricing of the American Dream, in which some of a family’s biggest expenditures — the ones that are foundations of long-term economic security and also the coveted rewards of hard work and striving — are often overwhelming.

Some of this is the legacy of a now-unwinding period of tight monetary policy, with the Federal Reserve’s campaign of rate hikes making mortgage and auto loan payments more daunting. But many of the forces bearing down on consumers have been gathering strength for much longer than that. College and child-care costs have been escalating for a generation, while eye-watering housing prices reflect a supply shortage more than a decade in the making.

Consumers are navigating those challenges at the same time as pandemic-era savings have faded and as a US labor market that recently seemed to have a job available for anybody has slowed.

It’s not universally bleak for consumers: Wage growth came alongside the pandemic labor shock, and the run-up in housing prices has been a wealth-building event for those who already own a home.

Still, voters have expressed a deep pessimism about the US economy in an election where they consistently name that issue as their top priority. And whether it’s Democrat Kamala Harris or Republican Donald Trump who wins in November, that economic discontent is likely to hang around.

That’s because the conditions appear to be creating a more lasting economic fault line in US politics, one that separates those who can afford a home or education from those who can’t.

“If people feel that they’re not able to achieve the American Dream, that’s going to shape who they support and what they support,” says Alexander Adames, a sociologist at Princeton University who studies the rising cost of joining the middle class and its effects.

The numbers are starkest when it comes to housing. The share of income needed to buy a home has soared as higher mortgage rates have collided with a supply shortage.

Eight years ago, it would have taken almost 14 years to save up for a 20% down payment on an median-priced home. Now, it would take 19 years.

The monthly mortgage payment on the median-priced house, meanwhile, has almost doubled from 14% of median income in 2016 to 26% this year.

That’s not just about high interest rates. The US has seen one of the most remarkable periods of home price appreciation in its history in recent years, says Zillow senior economist Orphe Divounguy. That’s increased the wealth of those who already owned a home and want to stay put. “It also makes it very, very difficult for most households, for most families, to go out and buy a home.”

Stuart Paul, an economist with Bloomberg Economics, says making down payments is “a tightening bottleneck on housing activity. And we think high prices and down payments are among the primary sources of consumers’ profoundly negative assessment of home-buying conditions — perhaps more so than rates.”

The state of the housing market is vexing Air Force veteran Jerry Sink and his wife as they contemplate buying a new home in Long Beach, California, after marrying last year.

Jerry Sink.Photographer: Jessica Pons/Bloomberg

“Rates coming down would help, but then there’s the run-up in housing values,” Sink said. “I can’t afford a house around here. Even on a VA loan, your monthly payment is going to be high. When I was just starting off, I was able to buy into the housing market with a reasonable down payment.”

At 69, Sink is nearing retirement. He’s also cobbling together three jobs — teaching for an online college, flying corporate jets and taking on freelance pilot gigs. After a divorce six years ago, he sold the home he owned with his ex-wife. The proceeds allowed him to pay down his credit card debt, but now those dollars aren’t available to help with a down payment.

It’s been hard work to keep his place in the middle class, Sink said. He’s also worried about what comes next. “I can handle unexpected expenses with freelance jobs, those help me afford vacations. But when I go into a fixed income, it’s like, ‘Okay, am I going to be able to do that? Can I help my kids when they ask?’”

Housing is only one factor in the economic stress. Car-related expenses are another burden, with pricier repairs and more expensive insurance adding to the strain of financing costs.

Car prices, too, have been taking a toll, said Greg Brannon, director of automotive research at AAA, which now puts the cost of owning a new car at about $1,000 a month compared with $774 before the pandemic. “Car ownership is almost inevitable for many people in the US. It’s something a lot of people look forward to. As Americans, we are accustomed to the freedom of mobility.”

One consequence of higher costs is that people are hanging on to their cars for longer. According to one industry estimate, the average age of passenger cars now on the road has risen to 14 years.

For Efran Menny, a 34-year-old teaching coach who lives in Houston with his wife and two sons, getting into the middle class means a constant juggling of costs and trade-offs. At $72,000, his family earns slightly less than the median household income in the US. His wife could earn more at a new job, but unless she could work from home, that would likely mean higher child-care costs, a common complaint for young families.

Republicans like Trump blame Harris and the Biden administration for the inflation of recent years. But Menny says he and his wife support Harris in part because of her pledge to bring down costs for middle-class families.

The child tax credit that the Biden administration pushed for during the pandemic gave Menny’s family a much needed boost. If it is brought back, as Harris has pledged to do, that might make it easier to pay for child care.

“I definitely am looking for the politician who is best going to promote the well-being of the family and the policies that are going to help the middle class the most,” Menny says.

At the same time, though, Menny is trying to save for his boys’ college education, while juggling a mortgage, car payments, grocery costs and medical debt. “I worry about having enough to do some things to equip my family with a better future,” he says. “If things keep rising and the price is so overwhelming, how are we going to compete with our salary?”

Then there’s what has happened to families’ balance sheets. American households are now sitting on a record $17.8 trillion in debt, $1.14 trillion of which is on credit cards, which tend to have relatively high interest rates.

The cost of a college education, traditionally the path to earning a middle-class salary, has risen rapidly, with yearly tuition at some elite schools reaching $90,000 – or more than $350,000 over a typical four-year stay. Some schools offer tuition breaks to families earning $150,000 or less. But more than 40 million Americans are already collectively paying back $1.6 trillion in student loans, a figure that’s more than doubled since 2010. And the interest rates on new loans have risen sharply in recent years.

Eric Huber, who works in manufacturing in Wisconsin, is now sitting on $80,000 in student loans, which he’s not sure he’ll ever be able to pay back. That, along with credit card debt, has been a drag on his finances and a key reason he feels like his place in the middle class seems tenuous.

The 45-year-old and his partner, who owns a salon, make between $50,000 and $70,000 a year, but the rising costs of rent and food have hurt. Meanwhile, he’s been in his job for seven years and hasn’t gotten a raise.

“It’s much harder to get into the middle class now — it all depends on the job you have and the education,” he said. “I’ve been poor my whole life but I’ve finally made it — and now my tax bracket may show that, but I still feel working class.”

In a Harris Poll conducted this summer for Bloomberg News, just 42% of middle-class Americans said the US economy was working for them. In a subsequent installment of the poll at the end of August, more than 60% of middle-class Americans said higher living costs such as rent or mortgages were hurting their financial well-being.

And while the Fed’s recent rate cut is a turning point, it is unlikely to spur immediate changes in behavior. Almost half of middle-class Americans said in the August poll that they planned to make a major purchase if interest rates came down. Though, among those preparing to buy something big, more than 80% said they would wait until rates fell below 5%. Almost a third said they would be looking for rates to sink below 3%.

Right now, 30-year mortgage rates are above 6%. Economists say anyone waiting for a return to the sub-3% mortgages is likely to have to wait for another crisis.

“At least in my lifetime, the only times I’ve seen huge drops in mortgage rates were the bursting of the dotcom bubble, the start of the global financial crisis and the start of a global pandemic,” says Divounguy, the Zillow economist.

Both Harris and Trump are acutely aware of voters’ economic dismay.

Harris has focused on what she calls an “opportunity economy” meant to bring down the barriers to joining the middle class and building wealth. She has promised to provide first-time homebuyers with $25,000 in down payment assistance and to spur the construction of 3 million additional new homes in her first term in office. Trump has said he would release more federal land for home construction and argued that reducing immigration and deporting millions of undocumented migrants, as he plans to, would ease demand for real estate.

But it’s unclear just how effective, or speedy, such measures would be in bringing home costs down significantly.

Trump’s broader economic sales pitch depends heavily on voters’ memories of pre-pandemic times when costs were lower. His plan hinges on juicing growth in the US by repeating his first-term agenda to reduce taxes and slash regulation while attacking imports with tariffs designed to bring overseas factories home to the US. His supporters argue that approach would mean higher incomes and an easier economic path forward for everyone. Even if he has offered only vague promises on the specifics to address things like health and child care costs.

Harris, in addition to her housing policies, has touted a $6,000 child tax credit to help parents cope, a cap on child-care costs for working families at 7% of income, and a $50,000 tax deduction for people starting small businesses, all ideas that would take the cooperation of Congress to implement.

What may in the end motivate voters is not the specific policy ideas, but whether they feel economic security might become more attainable.

Lisa Prescott, a 76-year-old grandmother who used to work in banking, moved to Ann Arbor, Michigan, with her husband, a retired CPA, a few years ago to be closer to her son and his children. They sold their Oregon home and bought a condo. Rising costs have left them budgeting more carefully and traveling less freely than they once did.

But it’s the future ahead for her children and grandchildren that she finds most worrisome. “People who are in their 20s and 30s and 40s — what's the prospect of them being able to purchase a home? These basics are becoming out of reach,” Prescott says. “I’m pessimistic about the future of a healthy middle class.” — With assistance from Gregory Korte

© 2025 Bloomberg L.P.