By Clare Ansberry

Aug. 28, 2023

The prime years for making smart financial decisions are, on average, 53 and 54.

At around that age, people have accumulated knowledge and experience about money, spending and saving, but haven’t begun losing key analytic cognitive skills. It’s also roughly the age when adults make the fewest financial mistakes, related to things like credit-card use, interest rates and fees.

iStock image

Knowing what leads to the financial strength of your early 50s is valuable. Younger adults can delve more deeply into basics like inflation and interest rates to hedge against lack of experience, and those who are older can work to keep their analytical skills sharp.

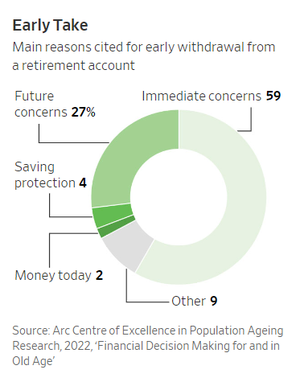

“As we get older, we seem to rely more on past experience, rules of thumb, and intuitive knowledge about which products or strategies are better,” says Rafal Chomik, an economist in Australia at the ARC Centre of Excellence in Population Ageing Research.

Chomik led a 2022 study that looked at financial literacy, which is the ability to understand financial information and apply it to managing personal finances. Financial literacy typically peaks at age 54 and then declines, according to the study.

The study gauged financial literacy using questions about inflation, interest rates and diversification. One question: If in five years, your income has doubled and prices have doubled, will you be able to buy (A) less, (B) the same, (C) more than today. (Answer: B)

People can—and do—make good financial decisions from their 20s to their 40s, as well as into their 60s and 70s. Chomik, who is 45, says some of his best financial decisions came earlier in his life and involved his 401(k)-type savings account. Contributions were mandatory when he started his first job at around age 18, but once enrolled, he actively chose funds that benefit those who have a longer investment horizon.

Financial decision-making requires a combination of reasoning skills that differ by age. Those in their 20s are better at absorbing and processing new information and computing numbers—so-called fluid intelligence—but don’t have as much life experience or crystallized intelligence—the accumulation of facts and knowledge. Crystallized intelligence tends to improve with age.

Getting help

Beverly Miller, a financial coach who often works with people who are in debt, says she did most things right before her 50s, avoiding credit-card debt, paying off car loans and paying off a 30-year mortgage in 12 years.

But she didn’t invest as wisely as she could have.

“We would let market changes scare us into making changes we shouldn’t have,” says Miller, 65.

Miller says she and her husband could have made more money if they had left it in growth funds. Likewise, she invested in rental properties, which she thought could be an easy source of income but weren’t.

It wasn’t until she was in her 50s that she and her husband finally turned to a certified financial planner to help with investments, she says.

“In your 50s, you have enough maturity and experience to know you need help,” says Miller.

Age of reason

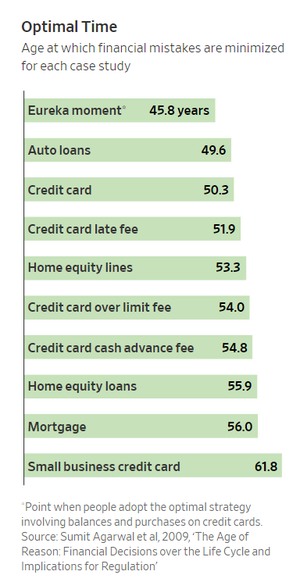

People make financial mistakes at any and every age, but they made fewer mistakes at the age of 53, according to economic researchers. In one study, economists looked at financial choices made by adults in 10 financial areas, including home-equity loans, lines of credit, mortgages and credit cards, and how those decisions affected fees and interest payments.

Fees and interest payments, across all 10 areas, are at their lowest levels around age 53, according to the 2009 study in the Brookings Papers on Economic Activity. That age was referred to as the “age of reason,” or the point at which financial mistakes are minimized. A financial mistake would include overestimating the value of a house, for instance.

At the age of 53, “people have been dealing with financial markets for years and know how to look for the right financial product, and minimize fees and payments,” says Sumit Agarwal, a professor of finance at the National University of Singapore and an author of the study.

Agarwal turned 53 this year.

“I have a lot of experience capital right now,” he says. “Going forward, I will be making more mistakes and will be slower making decisions.” People can keep their analytical skills strong and continue to make good decisions by reading and exercising the brain, he says.

One financial mistake 50-year-olds tend to make involves underestimating their life expectancy, which can lead to flawed planning decisions about retirement. A typical 50-year-old expects to live until age 76, when actuarial estimates have that person living another decade to age 86, according to Chomik’s study, which looked at surveys in Australia. A 2020 study in the U.S. found that 28% of adults 50 and older underestimated their life expectancy by at least five years.

Kristen Jacks, a 55-year-old financial educator based in New Haven, Conn., says people in their 50s have often experienced enough financial pain to make them more acutely aware of the need to weigh all financial alternatives carefully and avoid mistakes.

“You’re also at the age when you look at your retirement savings and realize you’re running out of years to make it bigger,” says Jacks.

She also works with younger people who can underspend as well as overspend. One young man in his 20s, she says, earned good money as a traveling nurse but was living in a small $600 a month apartment that he hated.

She says her own best financial decisions are lifelong habits. Jacks, who bought a $1,500 certificate of deposit when she was 15 using babysitting money, doesn’t accumulate credit-card debt and lives below her means.

“You do that for 20-plus years, and you are so much better off,” she says.

Write to Clare Ansberry at clare.ansberry@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.