Oct. 18, 2024

"ON PRESENT policies and performance, the United States is condemned to slower growth than the other main industrial countries for the foreseeable future.” So declared the Competitiveness Policy Council, a committee advising America’s president and Congress, in 1992, a time when America was gripped by concerns that its economy was declining and losing ground to Japan and Europe. The opposite turned out to be true. Japan entered a long period of stagnation, Europe’s growth fizzled and America experienced a mini-boom, fuelled by the rise of the internet.

iStock-157771817

More than three decades later, some are again painting pictures of an American economy heading towards decline. China is now the rising juggernaut in the East. Donald Trump, instead of Bill Clinton, is the candidate for president lamenting the state of the economy (Mr Trump says it is “failing”, where Mr Clinton called it an “unpleasant economy stuck somewhere between Germany and Sri Lanka”). Ordinary Americans are anxious. Gallup, a polling firm, regularly asks Americans if they are satisfied with how things are going. From 1980 until the early 2000s, a little more than 40%, on average, said they were. Over the past two decades that has dropped to 25%.

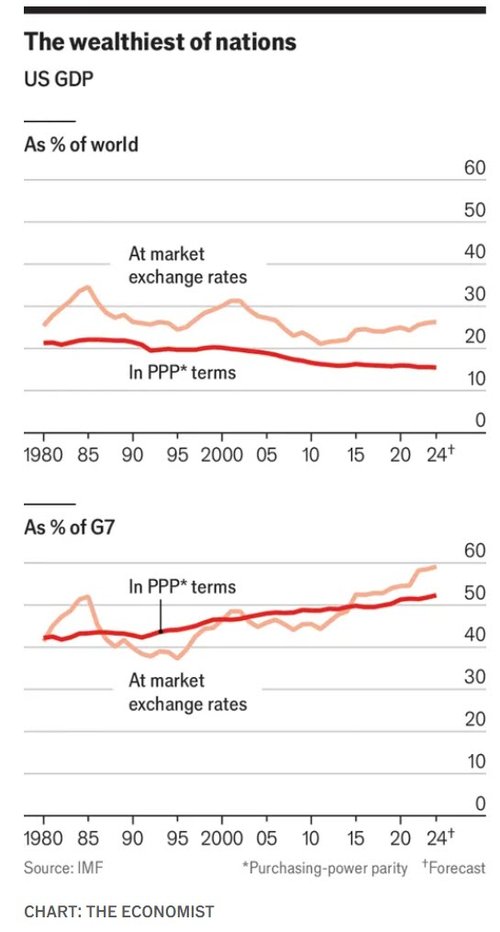

Are the prophets of decline onto something this time? Since the rollicking 1990s the American economy has suffered occasional upheavals, including the dot-com bust, the global financial crisis, a spike in unemployment during the covid-19 pandemic and, most recently, a surge in inflation. In purchasing-power-parity (PPP) terms America’s share of the global economy has indeed shrunk, from 21% in 1990 to 16% now.

America’s outperformance has accelerated recently

But one thing has been consistent since the early 1990s: America has grown faster than other big rich countries, and it has rebounded more strongly from bumps along the way. The faulty diagnosis of the competitiveness council back in 1992 should stand as a corrective for those now peddling gloom. America’s growth since then has been best-in-class, and its strengths today give grounds for optimism about the country’s economic power and potential. That America’s share of global GDP in PPP terms has decreased is less a comment on its own trajectory than on the growth spurts of the two most populous countries, China and India. China’s output per person remains less than a third of America’s; India’s is smaller still.

Even more striking is how America has outperformed its peers among the mature economies. In 1990 America accounted for about two-fifths of the overall GDP of the G7 group of advanced countries; today it is up to about half (see chart). On a per-person basis, American economic output is now about 40% higher than in western Europe and Canada, and 60% higher than in Japan—roughly twice as large as the gaps between them in 1990. Average wages in America’s poorest state, Mississippi, are higher than the averages in Britain, Canada and Germany.

And America’s outperformance has accelerated recently. Since the start of 2020, just before the covid-19 pandemic, America’s real growth has been 10%, three times the average for the rest of the G7 countries. Among the G20 group, which includes large emerging markets, America is the only one whose output and employment are above pre-pandemic expectations, according to the International Monetary Fund.

Coupling this growth with the dollar’s strength translates into heft for America and wealth for Americans. That can be seen in the huge numbers of Americans travelling and spending record sums overseas. A decade ago (as Chinese travellers too were demonstrating their wealth) many analysts thought that China would, by now, have overtaken America as the world’s biggest economy at current exchange rates. Instead its GDP has been slipping of late, from about 75% of America’s in 2021 to 65% now.

Endowed with gifts

This special report will explain why American growth has been so strong for so long, and why it can be expected to continue. Some of the reasons are down to the good fortune bestowed by geography. As a quasi-continental economy with a giant consumer market, American companies benefit from scale: a good idea hatched in California or product built in Michigan can, in short order, spread to 49 other states. America also has a big, well-integrated labour market, allowing people to move to better-paying jobs and drawing workers to more productive sectors. A long, porous southern border may be politically contentious but it has been an economic tailwind, allowing the labour force to steadily grow and helping to fill the hard, dirty jobs that many native-born Americans have no interest in doing. And as important as the size of the country is what lies beneath it. Over the past two decades the improvements in techniques for extracting hydrocarbons from once-unpliant shale rocks have turned America into the world’s biggest producer of oil and gas.

The American economy also has particular strong points which have bred more strength. Possessing the world’s deepest financial markets has made it easier for startups to raise equity, a better way to get off the ground than borrowing cash. The plethora of exciting young companies in America has, in turn, boosted the attractiveness of its markets. Similarly, having the world’s dominant currency has made global commerce more frictionless for American business. And America has the world’s best universities, which remain so in part by attracting the world’s best students.

The visible hand

Other policy choices have helped. America has a more relaxed approach to business regulation than many other countries. That has given high-tech companies room to play and grow. It also enabled the experimentation which led to the shale revolution. But America’s success is not just a story of small government. Officials have made bold, resolute interventions during crises (including ones that, in fairness, were abetted or exacerbated by lax regulation to begin with). After a shaky start, America delivered a strong response to the global financial crisis of 2007-09, acting decisively to clean up bank balance-sheets, and making aggressive use of monetary policy to support growth. The government’s response to the covid slowdown was yet more extraordinary, with a suite of fiscal stimulus packages that left other countries in the dust. Indeed, officials overdid it in their pursuit of a recovery, contributing to the global rise in inflation. But it is impossible to explain America’s mighty economic engine without acknowledging the government’s willingness to step on the accelerator pedal when it has sputtered.

For all of America’s prowess, it has plenty of maladies. A fundamental test of any country’s governance is whether its people live good, long lives. On this count America is wanting. In 2023 the life expectancy for a newborn American was 79, three years shorter than the average in western Europe, according to UN projections. That startling gap was virtually nonexistent in 1980. This is largely a reflection of fewer Americans reaching their dotage owing to obesity and to particularly acute American problems like opioids, guns and unsafe roads. But older Americans fare badly in relative terms, too. In 2023 in America the average 60-year-old was projected to live another 24 years, nearly one year shorter than in Europe. In 1980 the reverse was true; older Americans were projected to outlive their European peers by almost a year.

Many critics of America’s economic model contend that it is intrinsically flawed, beset by extreme inequality and ever-more dominant companies crushing competitors. But these are exaggerations. There may be scope for a fairer distribution of the country’s wealth without undermining America’s growth, but the widely held belief that the top 1% are taking it all is overdone. As for tech behemoths such as Apple and Amazon, their potential for dominance must be watched and, if necessary, curtailed, but it is also true that they have generated incredible value in daily life and shaken up stodgy industries. And they face fierce competition to stay on top. They stand as evidence more of America’s economic success than of its problems.

In the history of modern economics America’s three-decade outperformance is remarkable. Can it continue? Throughout this report we will consider reasons for pessimism, from poisonous politics to fiscal frailties. Set against these is a relentless dynamism, the essential characteristic of the American economy and the ultimate force propelling it forward. ■