By Eric Wallerstein

Jan. 22, 2024

Wall Street entered 2024 betting the year would go perfectly, but an up-and-down start for stocks and bonds suggests the going won’t be easy.

Some investors believe a strong economy could still boost stocks this year. PHOTO: MICHAEL M. SANTIAGO/GETTY IMAGES

Stocks have climbed to records, driven by cooling inflation that has spurred investors to anticipate as many as six interest-rate cuts. Falling rates often boost share prices by reducing the relative appeal of bonds and making it cheaper for companies and consumers to borrow, lifting corporate profits.

But despite Friday’s record close in the S&P 500, the rally in major indexes has stalled in recent weeks—the benchmark index is up less than 2% from where it was a month ago—while the labor market and economy show few signs of slowing. Bond yields have ticked up in the new year after falling sharply at the end of 2023.

This dynamic is prompting some analysts and portfolio managers to warn that further stock gains might be halting because the rate cuts that are widely expected to power the market higher might not arrive as quickly as bullish investors had wagered.

“Clearly, the consensus is that inflation is under control and we’re heading for a soft landing,” said Doug Fincher, a portfolio manager at New York City-based hedge fund Ionic Capital Management. “It’s certainly possible—but a lot of that is priced in.”

The S&P 500 is up 1.5% this year, but analysts see more signs of caution under the hood.

Investors have retreated this year from shares of banks, smaller companies and real-estate firms that posted big gains during the fourth-quarter rally, which was kicked off by investor belief that the Federal Reserve had pivoted in November to a rate-cutting stance. Bond yields, which rise when prices fall, have climbed as traders have pared back bets that Fed officials will start cutting rates in March.

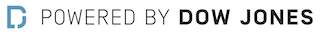

There is a greater than 50% chance the central bank keeps rates where they are at its March meeting, according to the CME FedWatch tool. At the start of the year, traders expected rates to end December around 3.85%. Now they expect closer to 4.1%, per futures contracts tied to the fed-funds rate.

Behind those moves: data showing persistent economic strength that could lift inflation. Treasury yields, a benchmark for borrowing costs, surged last week after Fed governor Christopher Waller cautioned against rushing to cut rates. Yields’ climb continued after data on retail sales, housing starts and unemployment filings all beat economists’ projections. The 10-year U.S. Treasury yield finished the week at 4.145% after starting the year at 3.860%.

Traders are now betting inflation will average above 2.4% over the next five years, the highest level since November, based on swap contracts tied to the consumer-price index.

The Russell 2000 index of small-cap stocks—which gained 22% in the last two months of the year—is down 4.1% in January. Speculative stocks have taken a beating; both Rivian and Coinbase have lost more than 25% after rising during the Fed-pivot rally. A KBW index of regional banks, which added 31% in November and December, has slid more than 3%. Shares of real-estate and utility companies are down even more, also having surged in those months.

The Bloomberg Barclays aggregate bond index, which soared in the final months of last year, is down 1.4% to start 2024.

“People tried to front-run the rate cuts by buying long-duration assets, like tech stocks and bonds,” said Nancy Davis, founder of asset management firm Quadratic Capital Management. “What if the Fed doesn’t cut that much or that quickly? Those people get hung out to dry.”

The Atlanta Fed’s GDPNow model shows the economy likely grew at a 2.4% inflation-adjusted pace in the fourth quarter. That is nowhere near the conditions that have historically necessitated rates coming down 1.5 percentage points—which traders were betting on heading into 2024.

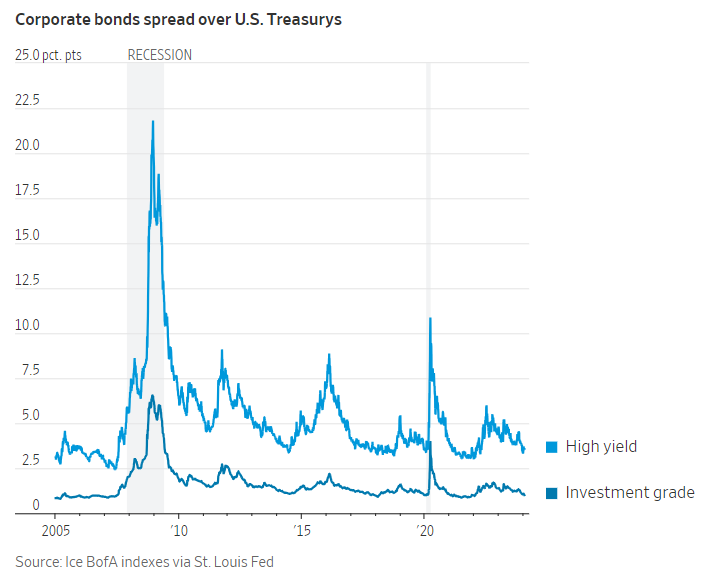

The extra compensation investors receive for buying high-quality corporate bonds over Treasurys is slimmer than before the Fed began raising rates, now around a percentage point. Credit spreads on junk bonds are similarly tight, signaling little concern over company defaults. Leveraged loans—used to fund private-equity buyouts or finance poorly rated companies—are in such high demand that companies are slashing their borrowing costs.

Some investors believe a strong economy could still boost stocks.

Sophia Drossos, an economist and strategist at Stamford, Conn.-based hedge fund Point72, expects robust consumer spending—and a proactive Fed—to help avert a recession and prop up corporate profits. The strong underlying U.S. economy “means risky assets can benefit,” Drossos said.

Not everyone is optimistic. Some fear new sources of inflationary pressure, such as trade disruptions from the Houthi attacks in the Red Sea and a drought in the Panama Canal.

And technical factors also could undermine the market gains. Interest-rate bets often represent investors protecting their portfolios against the risk of a recession or crisis that requires sudden rate cuts. Without a major slowdown, investors might remove those hedges, raising market rates. That could tighten financial conditions and disrupt stocks without any fundamental changes to the economic outlook.

But considering the strength of the economy, many doubt rate cuts will be as aggressive as investors hoped just a few weeks ago, threatening one of the rally’s biggest pillars of support.

“You’d think the wheels would have to come off to see that number of cuts,” said Fincher.

Write to Eric Wallerstein at eric.wallerstein@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.