By Bart Ziegler

April 12, 2024

Just a year ago, the car industry was nearly unanimous in its message: Electric vehicles are the future and will take over the market sooner than you think.

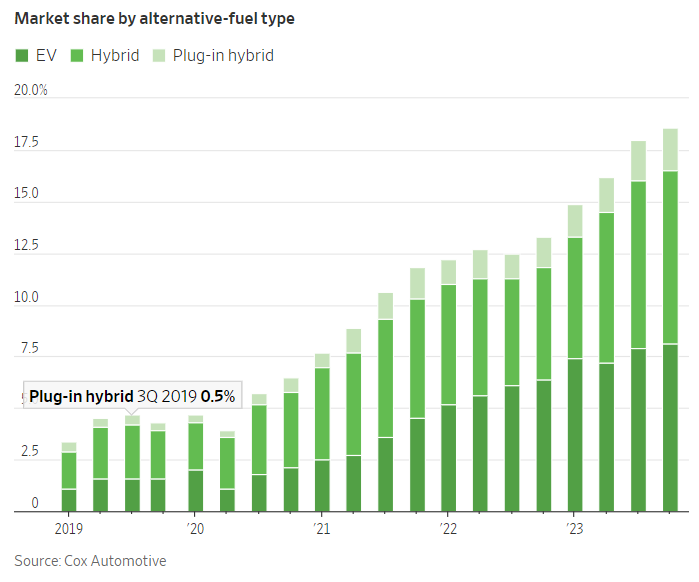

Now that optimism seems to have been premature. Though carmakers continue to roll out new EV models—those that run entirely on batteries and lack a gas-powered engine—their sales growth has slowed dramatically as consumers aren’t snapping them up as quickly as the industry expected. Unsold EVs are piling up on dealer lots despite price cuts.

iStock-1481143283

What happened? Many people worry that the shortage of public charging stations and limited EV driving range could leave them stranded with a dead battery. Once you find a charger, it takes vastly more time to refill batteries than a gas tank. And most EVs still cost more than similar gas-engine cars, especially since many models lost their tax incentives this year.

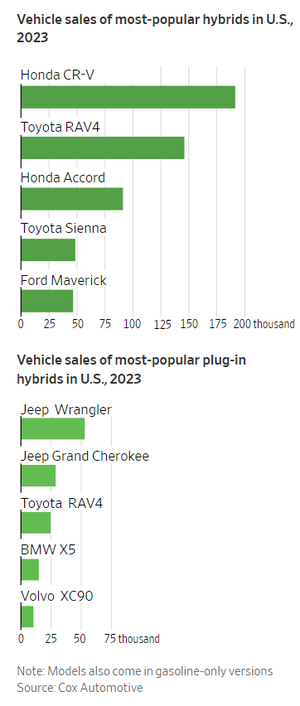

Instead, more buyers seeking to trim their gas bill or lower their contribution to greenhouse gases are turning to a quarter-century-old technology: hybrid vehicles, which combine batteries and an electric motor with a conventional internal-combustion gas engine. U.S. sales of hybrids topped those of EVs in 2023, about 1.4 million to 1.2 million, according to Cox Automotive, an information and technology provider for the vehicle industry. In response, carmakers plan to turn out more hybrids.

But how practical are these models? Will buyers save money? And which hybrid variation is best? Below, we answer these questions and others.

How do hybrid cars work?

In most hybrid vehicles, both the gasoline engine and an electric motor or motors can power the wheels. The engine also turns a generator that creates electricity. The electricity feeds into a battery pack, which in turn provides juice to the motor.

In addition, most hybrids recharge the battery in another way: When you take your foot off the accelerator or hit the brakes, the car reverses the direction of the electric motor, which both slows the vehicle and turns the motor into a generator to create electricity. This process is called regenerative braking. But this type of hybrid, the most common variation, can’t be plugged in to refill the battery.

Sophisticated electronics figure out whether the engine or motor—or both simultaneously in some models—should propel the vehicle at any time.

That sounds complicated. What’s the point?

Hybrids get more miles per gallon of gas because they aren’t burning fuel all the time—the engine can shut off while the battery and electric motor do the work, typically when traveling at lower speeds, coasting on the highway or in stop-and-go driving. Moreover, because the motor can assist the gas engine, the engine can be less powerful than in a similar gas-only car and thus more fuel-efficient.

How much better mileage does a hybrid get than a regular gas-powered car?

It can be dramatically better, about 40% more on average than gas-only vehicles, according to Consumer Reports.

The most efficient Toyota Camry hybrid sedan gets 52 miles a gallon in combined city and highway driving, according to the Environmental Protection Agency—nearly 63% more than the most efficient nonhybrid Camry’s 32 mpg. The hybrid Hyundai Tucson Limited SUV gets a combined 37 mpg, 32% better than the nonhybrid’s 28 mpg.

The Energy Department offers a tool to compare the mileage of hybrid and nonhybrid versions of the same model.

Are there other advantages to hybrids?

Many accelerate more quickly than their gas-powered equivalents. And they are quieter in low-speed driving when they run only on battery power. “They tend to drive a little nicer than their gas-only counterparts,” says Alex Knizek, manager of auto testing and insights at Consumer Reports. And despite their more complicated innards they can be more reliable than similar gas-powered vehicles, Knizek adds.

Moreover, unlike with an EV, “there is no change in the consumer experience,” says Stephanie Valdez Streaty, director of industry insights at Cox Automotive. “I don’t have to worry about charging, or range anxiety.”

So what’s not to love about a hybrid?

Most cost more than gas-engine models, up to 20% more, according to car-shopping site Edmunds, though they are less expensive than fully electric cars. For example, the base price of the Honda CR-V Hybrid, $34,050, is about 15% higher than that of the gas-only CR-V. Honda doesn’t make an electric CR-V, but a similar-size electric SUV, the Volkswagen ID.4, starts at $39,735.

But that price premium is falling as the cost of hybrids’ batteries and other components has declined. “I think we will continue to see hybrid premiums shrink,” says Valdez Streaty. However, there are no federal or state tax incentives for these non-plug-in hybrids.

Any other disadvantages to hybrids?

This isn’t necessarily a disadvantage but a quirk: They get better mileage in city driving than on highways—the opposite of gas-engine-only cars.

For instance, the Lexus RX hybrid gets 37 mpg in the city, but just 34 mpg on the highway. So if most of your daily driving is on an interstate, you won’t see the same efficiency benefit as people who do mostly stop-and-go drives.

What’s behind the lower highway efficiency?

The engine usually runs most of the time on the highway, burning gas, since the electric motor by itself isn’t powerful enough to maintain high speeds.

Can I earn back a hybrid’s price premium through gas savings?

Many owners can, depending on how long they keep the car and particularly if they do a lot of stop-and-go driving. Consumer Reports says the average payback period is four years when gas costs $3.35 a gallon and the vehicle is driven 12,000 miles a year. The more miles you drive or the more expensive the gas, the sooner the payback.

So should I consider a hybrid even if I do mainly highway driving?

Possibly, because most of them get better highway mileage than a similar gas-only vehicle. But your payback period could be much longer than for other types of drivers.

I’m confused by the “plug-in hybrids” some carmakers sell. What are they?

Plug-in hybrids, which the industry calls PHEVs, also combine a gasoline engine with an electric motor or motors. But their battery pack is much larger and so holds more electricity. And unlike a regular hybrid, you can plug them into a wall outlet or public charger to refill the battery, just as with an EV.

What’s the advantage of plug-in hybrids?

The added battery capacity means they can travel a certain distance on the electric motor only, ranging from 15 to 50 or so miles depending on the model. So around town or on short trips it can seem like driving an EV, with its silent ride and no tailpipe emissions. Once the battery is nearly depleted, the gas engine takes over and they operate like a regular hybrid, so there’s no worry about getting stranded.

The electric driving range means they can get greater gas mileage during a trip than an ordinary hybrid, but that depends on the length of the trip—a shorter drive takes more advantage of the gas-free range before the engine starts up—and whether it’s city or highway driving. Plugging them in at public chargers from time to time while on the road also boosts the mileage.

That efficiency is one reason carmakers plan to build more of them—plug-ins help their makers meet federal and state regulations.

What else might entice me to buy a plug-in model?

A few qualify for a federal tax credit, up to $7,500, while some states also subsidize plug-ins. Models eligible for a federal credit include the Ford Escape Plug-In Hybrid and Jeep Grand Cherokee 4xe. However, there can be income restrictions for these credits. Leasing a plug-in can be another way to get the value of the federal tax credit, since the leasing company gets the credit and can apply it to your lease cost.

Are there drawbacks to plug-in hybrids?

Yes. Absent a tax break, most cost more than regular hybrids—Toyota’s RAV4 Prime plug-in SUV has a base price of $43,690, compared with $31,725 for the regular RAV4 Hybrid. And in very cold weather, a plug-in is likely to run out of battery power faster than the stated range, the same shortcoming that affects EVs.

Plus, once you deplete the battery, you might get lower mileage than a regular hybrid, especially in highway driving. That’s because the extra batteries that plug-ins carry weigh hundreds of pounds more, eating up more fuel than an ordinary hybrid when in gas-engine-only mode.

What else should I know about plug-ins?

The plug-in feature brings the same charging issues EV owners face: You need at least a standard, 120-volt electrical outlet near where you park. And if you don’t spring for installing a 240-volt outlet at home, which can cost hundreds of dollars to well over $1,000, filling the battery could take 12 hours or so.

Moreover, you have to remember to plug it in—anecdotal evidence suggests that some plug-in owners don’t bother, since the cars run fine on gas. Of course, that means you won’t see the full gas savings, so the price premium you paid might have been wasted.

Given their higher price, who should consider a plug-in hybrid?

It depends on several factors. Do you have a place to plug one in where you live or work? Does your daily car use generally fall within the battery-driving range, or close to it, which will speed up the payback of the added sticker price? And do you live in an area with moderate electricity prices but high gas prices, which also makes the return on your investment come quicker?

The EPA offers a calculator that helps consumers figure out how much they would save on gas and spend on electricity with a plug-in.

So which type of vehicle power system provides the lowest fuel costs?

Generally an EV does, though there are variables including the prices of gas and electricity and your driving habits.

Here’s a comparison from the EPA of average annual fuel costs, based on 15,000 miles of driving, for several versions of Toyota’s RAV4 SUV: for the gas-engine version, $1,700 to $1,750; for the hybrid version, $1,300; and for the plug-in hybrid version, $950. There is no fully electric RAV4, but the similar-sized Volkswagen ID.4 AWD costs $750 a year in electricity, the EPA estimates.

Some carmakers offer “mild hybrids.” What are they?

These vehicles have a smaller electric motor and battery pack than regular hybrids, which they use almost entirely to supplement the power of the gas engine rather than propel the car independently. Some can shut off the engine while you slow the car and run briefly on the battery, and use regenerative braking to recharge the battery, like a hybrid. And in vehicles with a start-stop feature that cuts the engine while at a stoplight, the car resumes driving on battery power for a short period before the engine restarts. These features can raise the vehicle’s mpg rating, another boost to carmakers’ efforts to meet government requirements.

What are the downsides of mild hybrids?

They can’t drive solely with the motor except intermittently, which means they don’t offer the quiet and lively driving of a regular or plug-in hybrid in battery-only mode. And they don’t provide anywhere near the gas efficiency of these hybrids.

So what is better for the environment, driving any type of hybrid or an EV?

It’s complicated. While hybrids use less gas overall than regular gas-only cars, and thus put out fewer greenhouse emissions, they still pollute while in gas-engine mode. Some environmental groups have pushed back on carmakers that promote the green advantages of hybrids.

EVs, by contrast, emit no pollution themselves. But the electricity used to charge their batteries could come from coal- or gas-fired power plants that contribute to global warming, so in effect they aren’t totally clean, either, in those cases.

Bart Ziegler is a former Wall Street Journal editor. He can be reached at reports@wsj.com.

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.