By Ryan Dezember

June 20, 2024

Summer is off to a sizzling start, which means higher electricity bills are on their way.

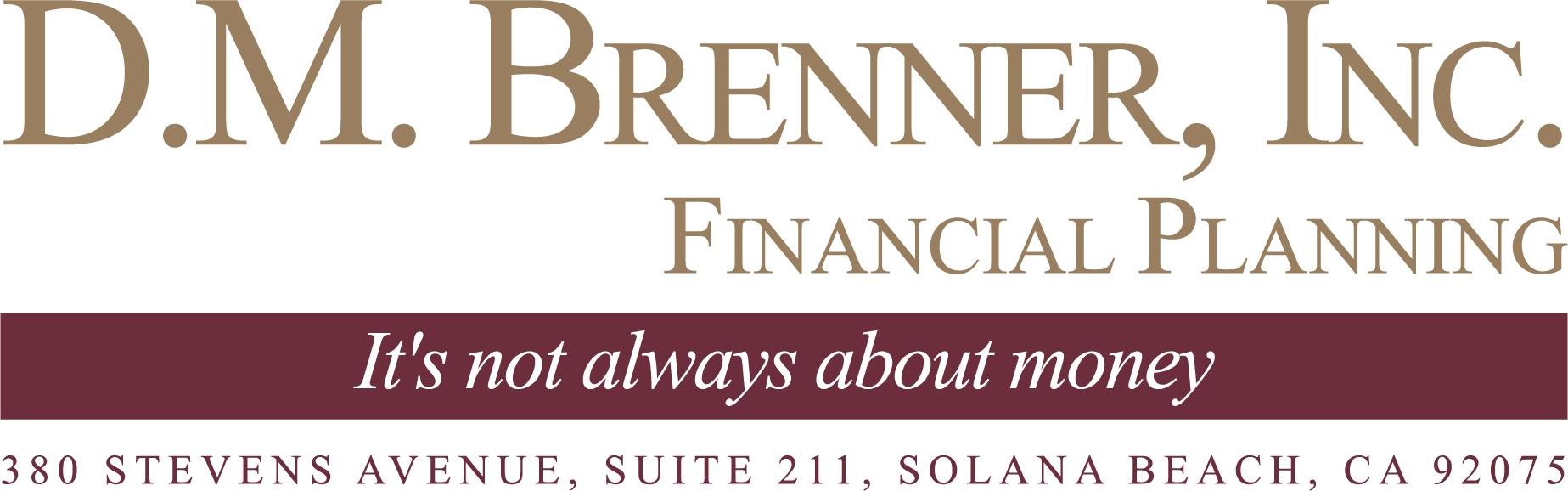

The Energy Information Administration expects the U.S. average monthly residential power bill to rise to $173 in June, July and August, up 3% from last summer.

The government’s estimates are subject to the weather, of course. But the biggest bumps in electricity expenses will likely occur along the Pacific Ocean and in New York, New Jersey and Pennsylvania. New Englanders can expect to receive smaller bills than in 2023, according to the EIA. So should residents of Texas, Oklahoma, Arkansas and Louisiana, who nonetheless can anticipate another summer of America’s biggest power bills, the EIA said.

The Southwest has been baking and a high-pressure ridge smothering the East is expected to bring triple-digit temperatures to Washington, D.C., this weekend for the first time since 2016. It snowed in Montana this week, but the Northwest is heating up and is forecast to join the rest of the country with above-normal temperatures next week.

This month will likely wind up being the warmest June in records dating back to 1950, both in terms of actual temperature and cooling-degree days, said Steve Silver, senior meteorologist at Maxar. Cooling-degree days are a population-weighted measure of temperatures above 65 degrees Fahrenheit that energy traders use to gauge demand.

“I wouldn’t expect a big change to a much cooler pattern for the rest of summer,” Silver said. “As far as whether we’ll be talking continued record heat, I think it’s a little too early to speculate on that.”

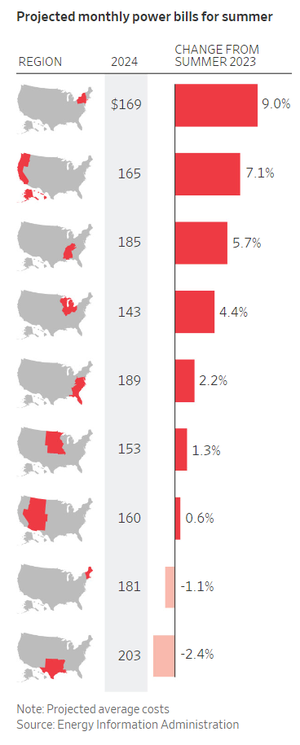

Air-conditioning season would be even more expensive had it not been so warm this past winter. With less need for heat, a lot of natural gas was left unburned. Prices plunged into spring, when demand for gas is low.

Though renewable energy production—particularly solar—is booming, burning natural gas remains the dominant means of producing electricity in the U.S. It accounted for 43% of utility-scale power generation last year, more than the next three biggest sources—nuclear, coal and wind—combined, according to EIA data.

Earlier this year, natural-gas futures hit their lowest inflation-adjusted prices since trading began on the New York Mercantile Exchange in 1990. Big producers, including Chesapeake Energy and EOG Resources, dialed back output to keep the glut from getting bigger and hold back gas until prices improved.

Chesapeake, for example, began curtailing its output in February when prices bottomed out, and has drilled but not completed wells and deferred connecting others to pipelines.

Chesapeake started April holding back about 500 million cubic feet a day, but has been slowly bringing that production back on line in recent weeks as prices improved, Chief Executive Nick Dell’Osso told investors Tuesday at a conference.

“When you think about the demand spike that we should see in the Northeast going into this weekend, as it’s going to be very hot, we would be ready with additional volumes to bring to market,” Dell’Osso said.

EOG throttled back output from its big new gas field in South Texas. The Houston-based company will wait to complete wells until later this year when new export terminals for liquefied natural gas are expected to open and lift demand and prices, Chief Operating Officer Jeff Leitzell said at the same conference this week in New York.

“Obviously that’s worked out,” Leitzell said. “We’ll see kind of what type of summer we have from a weather standpoint.”

The curtailments have already eaten into the glut. In late March, when prices bottomed, there was 41% more gas in domestic storage caverns than the five-year average for that time of year. Last week, the EIA data showed that stockpiles were down to 24% above the normal level for early June.

Gas prices have risen as inventories have been burned down. Futures for July delivery ended Tuesday at $2.909 per million British thermal units, up 85% from the low in late March.

Futures have recently traded even higher, rising last week above $3 for the first time since November. They retreated after developers of the Mountain Valley Pipeline told regulators that the 303-mile conduit was ready to move gas to market from prolific drilling fields in Ohio, Pennsylvania and West Virginia.

Write to Ryan Dezember at ryan.dezember@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.