Nathan Sheets

May 16, 2024

Current international tensions are concerning for markets but not unprecedented.

iStock-1398204765

The writer is global chief economist at Citigroup

Geopolitical pressures have posed unrelenting challenges for the global economy in recent years. Activity has been restrained by the Russia-Ukraine war, hostilities in the Middle East, and ongoing tensions between the US and China.

In tandem, populist political voices are gaining increased prominence in countries around the world. Such developments have, at least at times, disrupted commodities markets, put pressure on supply chains, shifted patterns of trade and capital flows and amplified uncertainties.

These recent challenges have led to perceptions that geopolitical pressures are becoming more frequent and severe. And some observers have argued that we’re entering a new regime in which economic fundamentals will take a back seat to geopolitical developments.

But clearly, previous generations also faced significant geopolitical pressures. Since 1900, these have included the first and second world wars, the cold war, the 1970s oil shocks and the 9/11 attacks. Geopolitical tensions arise inevitably from the posturing and competing interests of nations. Their ebb and flow has been a fact of life for generations.

A corollary is that, although geopolitical tensions are frequently in the headlines, there is little evidence that they have shifted to a more threatening tack. As such, the imperative for investors and policymakers is to remain circumspect — and to strike a balance between overreacting and underreacting to the ongoing parade of challenges that arise.

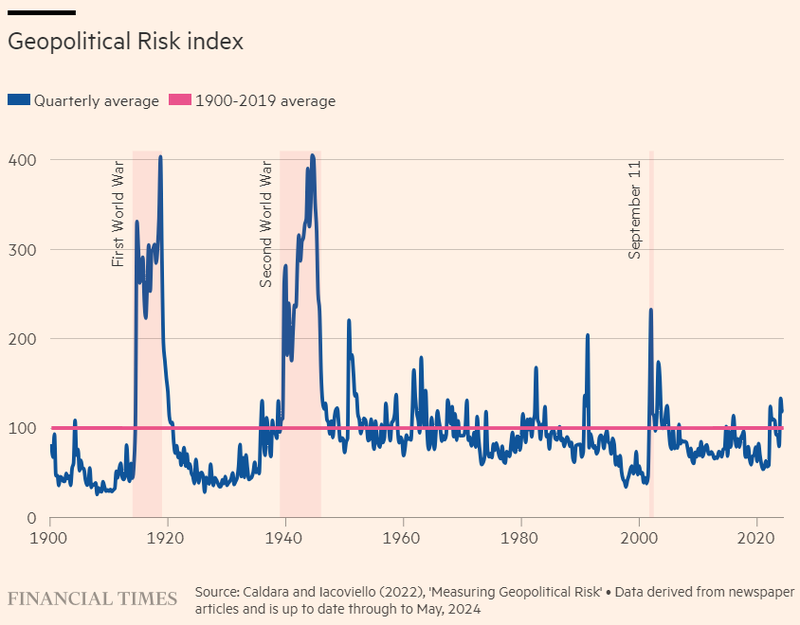

Work from two researchers at the Federal Reserve Board — Dario Caldara and Matteo Iacoviello — sheds further light on this discussion. They created an empirical index of geopolitical risk derived from text searches of English-language news articles from 1900 to the present. These searches are broad and include words such as war, peace, threat, boycott, sanction, blockade and attack. The resulting index represents an impressive step forward in understanding geopolitical risk.

By this measure, geopolitical pressures peaked during the world wars in the 1910s and 1940s. And they remained comparatively elevated through the 1950s and 1960s as the cold war took hold. More recently, the Russia-Ukraine war and Middle East tensions have lifted readings to the highest levels since the 9/11 attacks and related turmoil in the early 2000s. While these readings are up from the relatively quiescent 2010s, the overall average for the 2020s is just a bit above the centre of the longer-term distribution.

Thus, judged from this historical perspective, the index from Caldara and Iacoviello provides little support for the view that geopolitical shocks have become more frequent or severe. And, indeed, the data suggests that such arguments may reflect a hint of “recency bias” — the natural human tendency to place too much significance on recent events.

Echoing these observations, Citi colleagues and I examined the behaviour of financial markets during geopolitical episodes. Our key finding is that markets typically overreact to geopolitical events, with their initial imprint tending to be quickly reversed.

The markets’ upfront response reflects an uncertainty premium. Markets price in the expected effect of geopolitical challenges. But however bad things look, risk-averse investors are worried about “worse case” and “worst case” scenarios, and an uncertainty premium to compensate gets embedded in asset prices as well. As markets gain additional visibility into the shocks, the uncertainty premium tends to diminish and prices recover.

As such, we find that the best strategy for investors is generally to lean against the markets’ initial reaction to geopolitical events. While this finding is somewhat less true for the oil market, even there the data point to a “buy the rumour, sell the news” approach.

To be clear, none of this questions the severity of current geopolitical events or diminishes the need for investors to remain vigilant. The 2020s are shaping up to be a more difficult decade than the 2010s — and the 2030s may be more challenging still. In particular, we share concerns about the trajectory of the US-China relationship and the risk of increased global fragmentation.

Even so, we see little evidence that these tensions are more severe than would be expected drawing on the experience of the past century. The upshot is that even as these challenges continue to evolve, it’s too soon for investors and policymakers to “tear up the playbook” and seek entirely new frameworks for managing geopolitical developments.

Copyright The Financial Times Limited 2024

© 2024 The Financial Times Ltd. All rights reserved. Please do not copy and paste FT articles and redistribute by email or post to the web.

This article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream