By Heidi Mitchell

March 18, 2024

Young children may not even have an allowance yet, but thieves can make a lot of money off their identity.

Criminals can grab children’s information in the real world or online—most crucially, the Social Security number—and then use it to open a line of credit, using whatever address or bank account they choose. From there, the crooks can do anything from going on a spending spree to trying to claim the child’s government benefits like healthcare coverage or nutrition assistance. And since most parents have no reason to check their offspring’s credit, they might not find out about it until the child gets older and applications for student loans are rejected and benefits are denied.

iStock image

“Kids are particularly vulnerable,” says Ari Lightman, a professor of digital media and marketing at Carnegie Mellon University’s Heinz College of Information Systems and Public Policy. “And the theft of their identity can be a huge problem as they become an adult.”

Fortunately, there are plenty of steps to take to keep children safe from credit fraud or identity theft—and there are many ways to unwind any trouble that thieves cause.

Here is a look at some of the things parents need to know about how thieves steal information and how to deal with the dangers and consequences.

Grabbing the data

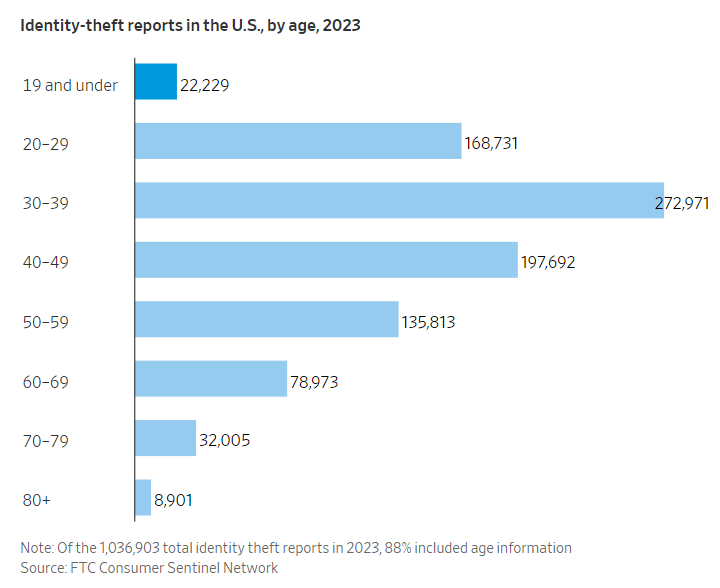

The Federal Trade Commission, the government agency responsible for assisting victims of identity theft, last year received 22,229 of such reports from Americans ages 19 and under, which accounts for 2% of all reported cases of identity theft. Those numbers have held pretty steady since 2020.

But Jennifer Leach, associate director of the FTC’s division of consumer and business education, says that identity theft can go undiscovered for a long time and unreported for a number of reasons—for instance, if the criminals are unscrupulous family members. “Our data is just the tip of the iceberg,” she says.

Scammers use many strategies to obtain valuable information about children. They might scour social-media platforms, search through data breaches, check public records, engage with the child directly in online forums or buy the information on the Dark Web. With just a few pieces of data, crooks can hijack children’s social-media accounts, intercept their physical mail, obtain low-limit credit cards in their name through retailers or access funds by changing passwords.

Gaining access to a Social Security number is considered the holy grail for thieves. “With that unique number, along with a couple of other bits of information, like a name, address and a birth date, a person can do all sorts of things,” says the FTC’s Leach. “They can get a loan, rent a house, sign up for government benefits, get utilities, a phone, a job—anything that requires a credit check.”

And since few parents ever check if their child has a credit report, it may be years before children come of age and realize they don’t have a high enough score to, say, rent an apartment.

“Unless you’re monitoring through an identity-theft protection service, you won’t know your child’s identity has been stolen until they apply for credit or a job,” says cybersecurity expert Domingo Guerra, executive vice president of trust at Incode Technologies, a company that provides virtual identity verification. “That makes them great targets for attackers.”

Freeze it fast

The first step to protect children is to freeze their credit, which restricts anyone, including the parent or child, from opening new credit accounts with the child’s Social Security number. The sooner people can do it the better—in fact, they can enact a freeze as soon as the child is assigned a Social Security number.

“Honestly, there’s no downside to keeping a child’s credit frozen or even freezing it when they are a baby,” says the FTC’s Leach.

To place a freeze, contact each of three credit bureaus—Equifax, TransUnion and Experian—and ask them to check your child’s credit. “If there’s no credit report, good. There’s no fraud,” says Leach.

Then ask them to freeze the child’s credit. “That means they’ll create a credit file for your child and then freeze it, which will stop anything from happening in their credit file,” she says. (After children turn 14 or 16, depending on the bureau, they must do this themselves.)

From there, sign up at annualcreditreport.com to get a report from all three bureaus as often as weekly—a service that has been made free on a weekly basis permanently since the pandemic—to check for suspicious activity. Also set up a fraud alert, which sends notices to potential creditors, requiring them to take extra steps to verify a person’s identity before allowing anyone to open a line of credit in their name. Parents need to contact only one bureau to get an alert; it will alert the other two. (The alerts are free, but must be renewed annually.)

Question everybody

As children get older, there are ongoing steps to take to protect their vital information. Don’t overlook a very basic move: Lock their birth certificate and Social Security card someplace safe, like a cabinet or safe, and if documents are stored in the cloud, be sure to use a password manager and multifactor authentication to gain access to those files, says Max Anderson, chief growth officer at 360 Privacy, a company that deletes information of customers off the internet.

Meanwhile, be very cautious when asked to share a child’s information, a Social Security number in particular. “If your child needs to get a passport, a job, or pay taxes, they’ll need to share their Social Security number in the process,” says Leach. Opening a new bank account will also require that number. “But never [share it] with anyone who calls, emails or texts and asks for it. Always be skeptical, always give it to someone through a secure means,” Leach cautions.

When a school or sports team or even doctor’s office asks for the number, push back. “Ask why they need it,” Carnegie Mellon’s Lightman says. “If they do, ask who has access to it, how it’s secured and stored and for how long.”

“Prevention is always easier than remediation,” says Incode’s Guerra. “If data can’t be accessed, or is not collected in the first place, by definition it cannot be stolen.”

Keep quiet

The next crucial step involves something that is much harder to control but is ultimately a parent’s responsibility: how children handle themselves online.

“Parents should know how much information their children are disclosing online,” says Lightman, noting that this can be nearly impossible to understand in totality. “We’re talking about Gen Alpha here. Their digital footprint starts when they are born.”

Lightman recommends the online-safety section of the website for the nonprofit Common Sense Media to get information and advice about the identity-theft dangers online. And there are plenty to inform children about. Warn them, in a way that will resonate with a young person, about the troves of data that social-media sites collect, and how hackers could use the information to gain access to their accounts. Encourage them not to fill out online personality quizzes, whose primary focus is often data mining. Advise them not to give too much away while playing on collaborative game sites, and explain how “friends” made online may not be so well-meaning.

“There needs to be common ground and a shared understanding between parent and child about what to post, what not to post, in which channel and with whom,” he says. “The difficult part is when a child knows they are being monitored, they might hide activity from their parents.”

He recommends providing access to social media through “mediated” accounts—such as Instagram Supervision or Snapchat Family Center—which often provide a set of tools and insights that parents can use to help their teens navigate social-media engagements. Parental oversight is an opt-in feature and the teen typically has to agree to participate. Studies have shown these types of accounts and conversations lower chances of victimization.

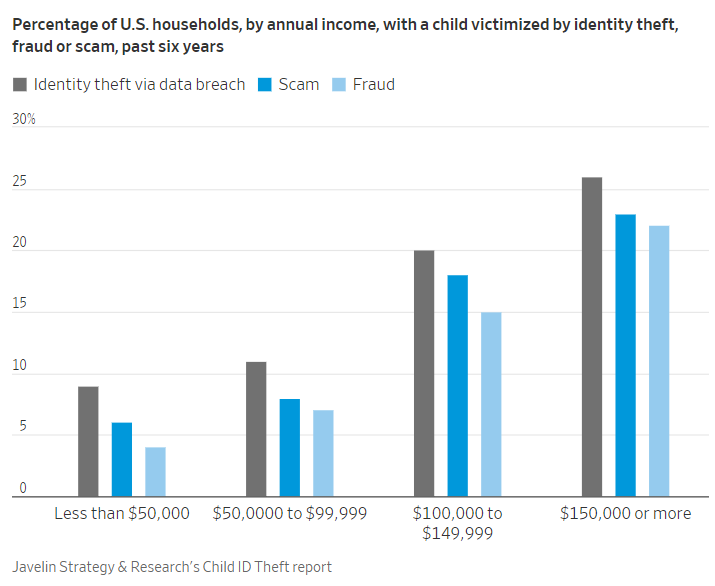

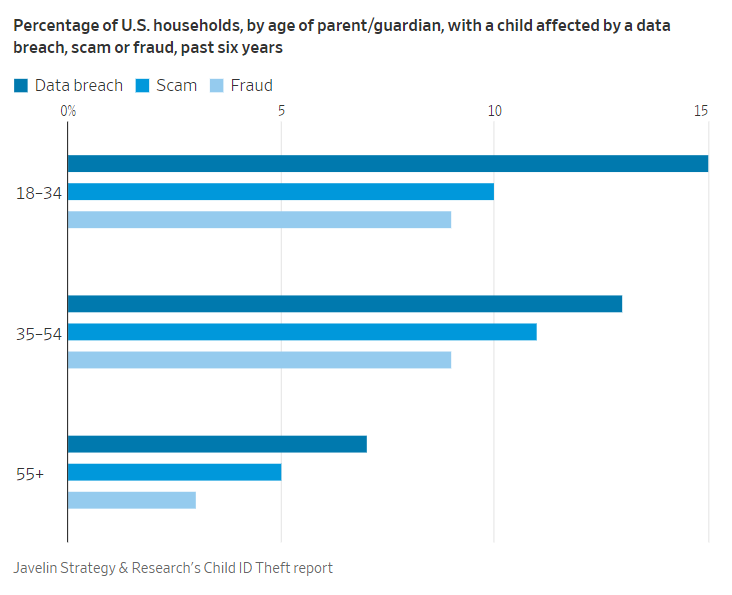

Parents should also recognize how much they themselves expose about their children on social media. “Parents’ social-media behavior puts their kids at risk,” says Tracy Kitten, director of fraud and security at Javelin Strategy & Research, and author of the consulting firm’s 2023 Child ID Theft report. “They post where their kids go to school, what sports they play, their names, their birthdays.”

Armed with that information, “a bad actor could start building a persona or profile, or ‘synthetic identity,’ that mimics the child’s persona or identity,” Kitten says. From there, she says, the mimicked or fake credit profile could be used to apply for benefits or open new accounts under the child’s name or using parts of that child’s identity.

“I’ll be honest, I write about this stuff and I’m guilty of [posting] it,” she says.

Fixing the damage

But let’s say the worst happens: Parents believe a child’s credit is compromised. Now what do they do?

Think back to any warning signs that might help determine how far back the problem goes. “Any offers from credit-card companies, auto-insurance providers or strange phone calls, like Bank of America asking for your five-year-old, is cause for concern,” says Michael Bruemmer, vice president of global data breach resolution and consumer protection at Experian.

Parents might get notice of bills that are unpaid, or preapproved credit in their child’s name or a letter from the IRS stating the child hasn’t paid taxes, says Leach. “You might get a notice of denial for government benefits or healthcare because you’ve already ‘claimed’ them,” she says. “These are signs that it’s time to start undoing the damage.”

If parents suspect their child’s identity has been stolen, Leach says, the first thing to do is call the companies that have extended credit in the child’s name. Tell the companies to send written confirmation that the account is closed right away. “You want them on notice immediately that this is fraud,” says Leach, adding, “Act quickly, report what you know, keep notes, if anything must be delivered by mail, make sure you send it certified.”

Many creditors will want a theft report—an official document from the FTC showing that an identity theft has been reported—which parents can obtain at identitytheft.gov. Once a parent reports the identity theft involving their child, they will be given a customized recovery plan that tells them the steps they must take—from writing letters to correct the credit report to replacing Social Security cards.

The whole nightmare can often be unwound in 30 days, experts say, but sometimes it can take years for more complex thefts, including if crimes were committed under the fraudulent identity.

“If someone bought a house in a child’s name, it can take a while to unwind. If someone opened a credit card in their name, it should take less time,” says Leach.

Heidi Mitchell is a writer in Chicago and London. She can be reached at reports@wsj.com.

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.