By James Mackintosh

Dec. 29, 2023

It is good practice to learn from your mistakes, but even better is to learn from other people’s mistakes. My biggest error in 2023 was the same as everyone else’s: being in the consensus that the fastest rate hikes in 40 years would cause a recession. They didn’t, but there is still deep disagreement on why—and the direction of your portfolio depends on the answer.

brendan mcdermid/Reuters

As a reminder, at this time in 2022, predictions of recession were the norm—and on some measures stronger than they had ever been outside an actual recession. I wasn’t persuaded by the economic models, because they paid no heed to the effects of the pandemic on supply and demand. But I thought it unlikely that the nascent stock rally would continue, because it was a bet on inflation’s coming down without the economy being hit. How likely is that? Not very. Except that it happened.

To get a lesson, we have to decide why the economy defied expectations, and here’s where it gets tricky. There are at least four competing explanations, with quite different investment recommendations:

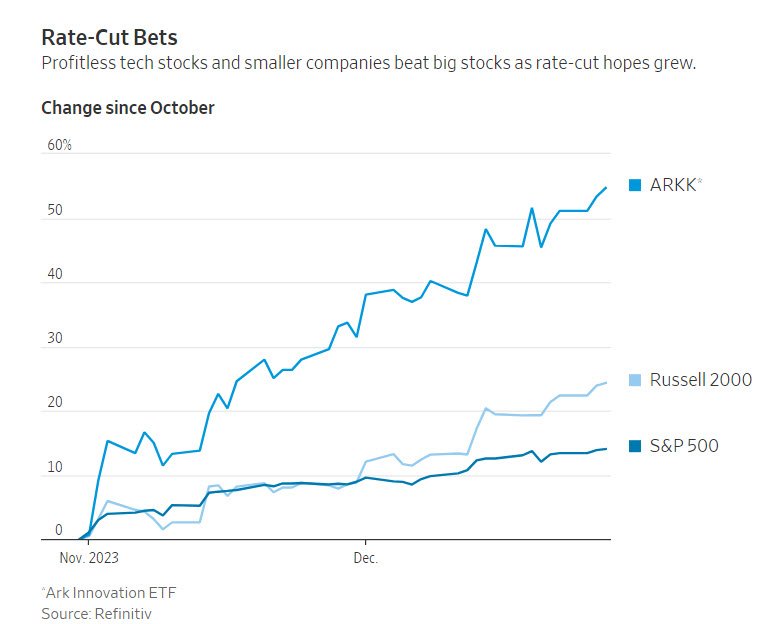

• Supply disruptions caused by the pandemic went away, and the shifts in demand to goods, then back to services, have begun to even out. As demand and supply matched again, price increases slowed. According to this view, the Federal Reserve never needed to raise rates so fast, and can now cut rapidly. Buying into this explanation, investors have spent the past few weeks vacuuming up the stocks of the weakest and smallest companies on the assumption that they’ll be the biggest winners from rate cuts.

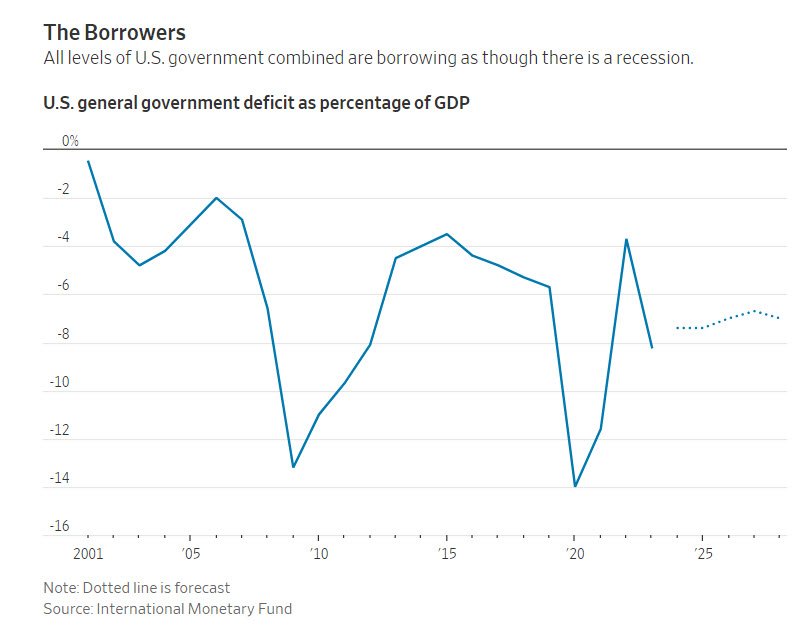

• The government filled the gap. Massive unfinanced spending means all levels of U.S. government will run a deficit of more than 8% of GDP in 2023, according to the International Monetary Fund. That is by far the most of any developed country and a huge increase from 2022’s 3.7%. Had the government cut spending or raised taxes to compensate for the primary causes—a plunge in tax revenue and rise in interest costs—it surely would have created a recession, and new green subsidies boosted growth as companies built new facilities. The government can’t run such huge deficits forever, however, and either higher taxes or less spending will weaken the economy and profits in the future.

• Rates didn’t bite. Homeowners who refinanced their mortgages at record-low rates—combined with investment-grade companies locking in cheap financing for the longest in decades—stopped the Fed’s rate increases from hurting much. There was pain for those with floating-rate loans: Auto-loan and credit-card delinquencies are on the rise, as are defaults by companies in weak business lines such as office rental. The same goes for banks that have to pay more on deposits than they are getting on bonds they bought when rates were low. But the core of the economy has been fine and perhaps even better off than before thanks to those higher deposit rates. Junk-bond investors who bought at the right moment got both high rates and low defaults, a great combination—but only if it continues.

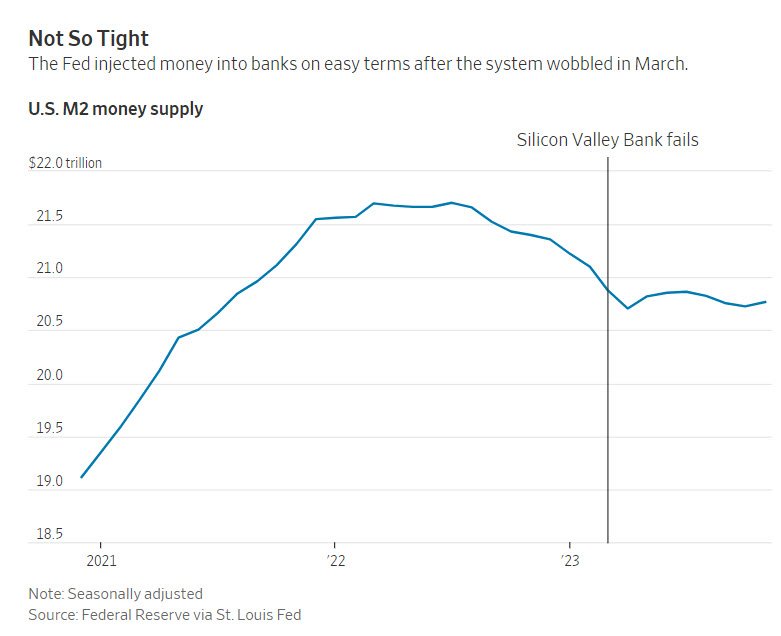

• The Fed offset its own tightening. Lending on easy terms, the Fed stepped in to rescue regional banks in March after the collapse of Silicon Valley Bank. While it kept raising rates, the money supply stopped shrinking at that point and is now the same as it was then. In terms of the quantity of money, the Fed was no longer tightening policy, even though the price of money, the interest rate, kept going up. The Fed’s boost definitely helped the banks, while the extra money helped lubricate the economy, but economists differ on how much it matters compared with interest rates.

What happens next depends on which of the four explanations had the most effect in 2023. I suspect all played a role, but none will continue, at least for long. Transitory effects are, well, transitory. While we can’t be sure they are over, they can’t last forever.

Government spending is unlikely to be scaled back drastically in an election year, and taxes certainly won’t rise. But after that, the deficit will need to be tackled. Interest rates will have a creeping effect as more companies refinance. And the Fed’s special lending program for banks expires in March.

Put it all together, and the outlook is for weaker growth, which is bad for stocks, and lower rates, which are good for stocks. Exactly how they will combine is the bet. The big lesson from 2023’s mistake is that all four of the effects were a surprise to most, and 2024 will surely bring more.

There are always new mistakes to make. But in 2024, bear in mind one of the oldest lessons: It is riskier to buy stocks when they are expensive because they offer little margin of safety to absorb bad news. Things can always work out but, with U.S. stocks so expensive already, the odds aren’t good.

Write to James Mackintosh at james.mackintosh@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.