By Nick Timiraos

April 29, 2024

Amid the debate over whether and when the Federal Reserve cuts interest rates, another important argument is unfolding: where do rates settle in the long run?

At issue is the neutral rate of interest: the rate that keeps the demand and supply of savings in equilibrium, leading to stable economic growth and inflation.

Fed discussions over the neutral interest rate—a theoretical ’just-right’ level where growth is stable and inflation is in check—could affect a wide range of asset prices. PHOTO: MORIAH RATNER/BLOOMBERG

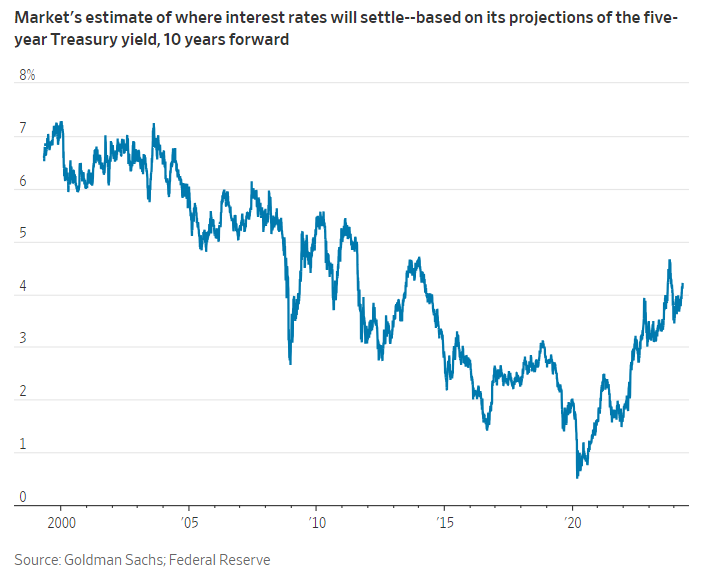

For the last 40 years, and especially following the 2008 financial crisis, economists and Fed policymakers steadily revised down their estimates of neutral. This view became embedded in bond yields, mortgage rates, equity prices and countless other assets.

But now, some see reasons for neutral rising, with the potential to change a wide range of asset prices.

The neutral rate, sometimes called “r*” or “r-star,” can’t be directly observed, only inferred. Five years ago, after the Fed raised its benchmark federal-funds rate to 2.4%, officials saw signs of feeble growth and inflation and began lowering rates—implying neutral must have been around that level, or lower.

But when the Fed raised the fed-funds rates to 5.3% last year, the highest since 2001, the economy appeared to shrug it off, giving reason to think neutral might be higher. “The economy has weathered this exceptionally well. No one could have told me 10 years ago we would have raised rates to this level with this outcome,” said Joe Davis, chief global economist at Vanguard. “Our conviction in a higher neutral rate is going up as every quarter of data comes in.”

Higher neutral, or just lags?

The persistence of strong demand doesn’t necessarily mean neutral has risen; it may simply mean higher rates have yet to work their way through the financial system. Households and businesses, having locked in their borrowing at low rates, may be relatively insulated from the recent rise in rates.

Based on the resilience of economic activity to higher interest rates, “one conclusion you could draw is that r-star must be higher. Another conclusion you could draw, which I think is totally valid based on seeing the same set of information, is that the economy is just not that sensitive to interest rates,” said Kris Dawsey, head of economic research at hedge-fund manager D.E. Shaw.

Modeling the effects of interest rates therefore requires not only an estimate of neutral, but also of how sensitive spending is to rate changes and the lag between spending and prices.

“That’s a lot to get right, especially when errors in one area can easily be mistaken for mis-estimates elsewhere,” said Jason Thomas, chief economist at private-equity manager Carlyle Group.

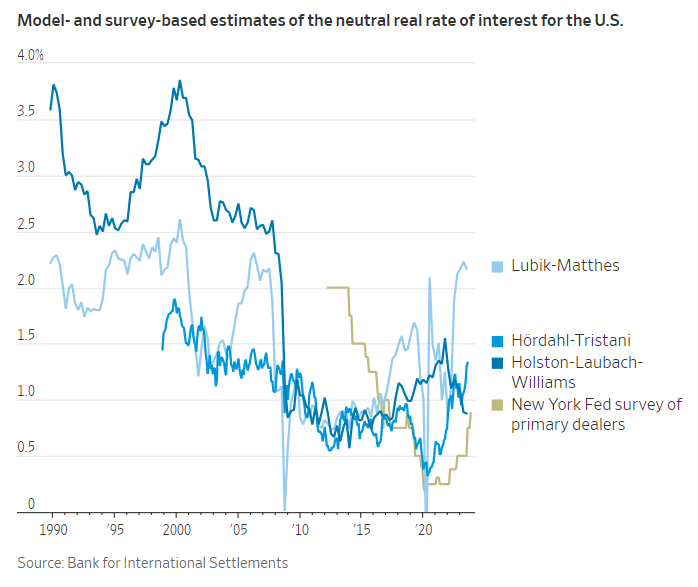

Every quarter, Fed officials project the longer-run interest rate, which is, in effect, their estimate of neutral. Their median estimate declined from 4.25% in 2012 to 2.5% in 2019. After subtracting inflation of 2%, that yielded a real neutral rate of 0.5%.

The median then crept up to 0.6% in March, though that understates the amount of movement in those estimates. In March, nine of 18 officials put neutral above 0.5%. Two years earlier, just two did. Cleveland Fed President Loretta Mester said after years of penciling in a long-run rate estimate of 2.5%, she revised her projection last month to 3%.

The implications for the Fed

The debate over r-star may have little near-term effect on the Fed because current interest rates are above virtually all estimates of neutral. That means they are restraining growth and prices, and more likely to fall than rise. If growth remains solid and inflation stubborn, it may lead to speculation neutral has risen, and thus current interest rates aren’t that tight. And thus, the Fed has less reason to cut rates.

Alternatively, if inflation resumes its decline, questions about neutral would drive how much the Fed ultimately cuts rates.

The Fed wants to “normalize policy, but ‘normalize’ to where?” said David Mericle, chief U.S. economist at Goldman Sachs. “They are not going to stay in the 5s, but normalization is not going to take them all the way to 2.5%. Where in the 3s or 4s they feel comfortable stopping is still up in the air.”

Reasons for a higher neutral rate

There are several factors cited for why neutral may be rising: soaring government deficits and strong investment driven by the green-energy transition and an artificial-intelligence-fueled frenzy for electricity-intensive data centers. Higher productivity from AI could also lift long-run growth and the neutral rate.

Dallas Fed President Lorie Logan warned in a recent speech that interest rates may not be as restrictive as believed because of a higher neutral rate. “Failing to recognize a sustained move up in the neutral rate could lead to over-accommodative monetary policy,” she said.

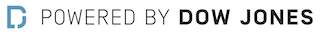

Investors have already concluded interest rates aren’t likely to return to the low levels that prevailed before the pandemic. Interest-rate futures suggest the fed-funds rate will stabilize around 4% in coming years.

‘We only know it by its works’

Others are skeptical that neutral is rising. New York Fed President John Williams, who co-wrote a widely followed model of r-star, has said he expects an aging global workforce that boosts savings to keep neutral low.

Fed Chair Jerome Powell and some colleagues have suggested that economic strength could as easily be explained by idiosyncrasies of the pandemic, such as a boost in the supply of workers last year from immigration. “It’s not that the policy isn’t restrictive and it’s not responsive to rates. It’s that we’ve had this outside force that is temporarily affecting that,” Powell said at a talk this month.

Fed governor Christopher Waller has said he thinks r-star is around 0.5%. “You have to explain to me why real rates on safe, liquid government debt fell for 40 years and why suddenly it turned around,” he said last month. “No one has really given very good answers to that.”

Several economic models attempt to estimate neutral, but they have wide error bands and are prone to revision.

Given the imprecision, Powell has implied the Fed must act on the assumption it doesn’t really know where r-star sits. “We only know it by its works,” he said last year.

Write to Nick Timiraos at Nick.Timiraos@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.