By Bill Alpert

June 27, 2024

The day is approaching when your wristwatch may send you to the hospital.

The first portable electrocardiograph was an 85-pound backpack. Today, a 10-gram patch stuck on your chest can transmit ECGs nonstop for two weeks. There are 100 million people who wear an Apple Watch, which can alert them to irregular heartbeats along with their text messages.

Wearable sensors on arms, wrists, or fingers can now report heart arrhythmias, glucose levels, blood oxygen, and other markers of health. A grander vision laid out in medical journals sees wearables monitoring the chronically ill without constant hospital visits. They could detect hidden health problems before they cause a stroke or diabetes.

iStock image

Two converging forces are marrying health technology and wearables. Tech giants like Apple and Alphabet’s Google are adding health features to their products. Medical-technology specialists—like the ECG patch maker iRhythm Technologies or glucose-monitor makers DexCom and Abbott Laboratories —are taking their devices beyond the clinic.

“In this sensor world, people start on the consumer side and want to move into healthcare,” says DexCom CEO Kevin Sayer. “We on the healthcare side are trying to go down more toward consumers. I think all these things are kind of crashing together.”

The early betting favored the tech giants; every health announcement by Apple, Google, or Samsung Electronics hit the medtech stocks. But it takes sustained investment in clinical trials to change what doctors do. Big Tech companies have cut back on their healthcare investments. It now looks like the medtech specialists will be the vanguard of the digital health revolution—with smartwatches and smart rings bringing them more customers to diagnose.

“A group of digital-health-focused medtech companies are coming of age and reaching a level of scale where they can not only be profitable but also invest to compete with bigger tech players,” says Blake Goodner, co-founder of the healthcare-focused hedge fund firm Bridger Management.

The tech giants aren’t getting out of the health business. Apple’s smartwatch has an electrical heart-rate sensor that generates a single-point electrocardiogram, a wrist-temperature sensor, and an accelerometer that detects hard falls. Hundreds of millions of people are wearing smartwatches with health features from Apple or rivals Samsung and Garmin.

In 2018, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration cleared the Apple Watch to alert its wearer if an irregular heartbeat might be atrial fibrillation, a serious condition that raises the risk of stroke and heart failure. It isn’t hard to find stories of people who went to their doctor after an Apple Watch alert, with the medical work-up confirming AFib.

Meanwhile, Ōura has sold more than two million smart rings that measure heart rate, temperature, blood oxygen, and sleep patterns. A smartwatch must come off the wrist for charging overnight, says Ōura’s vice president of healthcare, Jason Oberfest, while a ring can stay on for a week between charges. “The watch is another screen strapped to you,” he says. “Our ring just kind of disappears into the background.”

Advances in sensors and digital processing are also driving some of the fastest-growing companies in medical technology. DexCom stock shot up from $10 a share to $165 in the four years through 2021, as doctors and health insurers backed its stick-on continuous glucose monitors for diabetic patients on insulin. The stock of iRhythm went from $30 to $285 over a similar stretch, as its Zio ECG-patch won most of the medical market for the long-term monitoring that determines if heart flutters actually are AFib. Both stocks are down from their 2021 peaks, but they remain favorites among medtech investors.

“Wearable sensors have disintermediated the diagnostic from the bricks-and-mortar visit,” says Dr. Mintu Turakhia, who left his post as director of Stanford University’s Center for Digital Health last year to become iRhythm’s science chief. “We had been doing it before, then Covid accelerated it.”

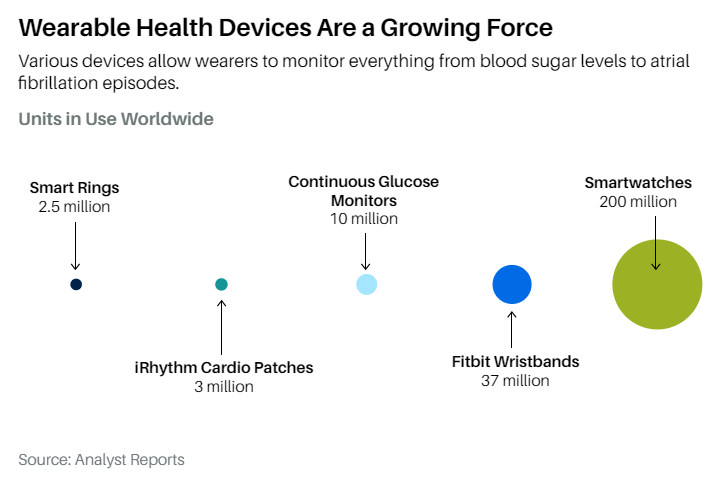

Still, the population of clinical-grade wearables is small compared with hundreds of millions of smartwatches or the nearly 40 million Fitbit wristbands. IRhythm will sell about three million ECG patches this year, while DexCom and Abbott will sell about 10 million glucose monitors.

With nearly half of U.S. adults wearing a smartwatch, doctors are looking for ways to leverage that patient-generated data. The Apple Watch costs $400 or more, but that’s still cheaper than dedicated clinical sensors. Donated or shared devices could bring cardiac monitoring to communities that lack healthcare facilities, says Dr. Rohan Khera, clinical head of the Yale New Haven Hospital’s Center for Health Informatics and Analytics.

Yet many doctors don’t know what to do with the Apple Watch ECG strips that pour in from their patients, says colleague Harlan Krumholz, a cardiologist who runs the Yale New Haven Hospital Center for Outcomes Research and Evaluation. “We’re in an awkward adolescence, where we are not yet gaining the benefits of what these devices can do,” he says.

Doctors already feel overworked. Now patients want them to interpret smart-device readouts with no added reimbursement, says Richard Milani, a cardiac-care doctor who is the chief clinical innovation officer at the Sutter Health system in Northern California. He is building a team there that will monitor sensor traffic from chronically ill patients and integrate the findings into the records of the primary care doctors.

There are some good reasons why technologies diffuse slowly into medical practice. The FDA requires proof of safety and effectiveness for any device intended to diagnose or treat a medical condition. That can entail long, expensive clinical trials. Then, medicine’s professional societies decide whether to add a new treatment to practice guidelines. Finally, payers like Medicare decide whether to reimburse for it.

So, the Big Tech companies focus on things a consumer can use, while making no claims to treat or diagnose, says Mark McClellan, a former head of the FDA who runs the Duke-Margolis Institute for Health Policy.

At a public workshop Wednesday by the FDA and the Digital Medicine Society focusing on clinical trial use of patient data from medical devices, agency and industry speakers said they hoped wearable sensors would become routine parts of medical trials and patient care in the next five years. The FDA’s Digital Health Center of Excellence medical chief, Matthew Diamond, tells Barron’s that he hopes responsible innovation in wellness and medical devices will shift healthcare from reaction to prevention.

Back when Apple and Alphabet first rolled out digital health products around 2015, they had plans to disrupt medical practice. One Apple project explored whether the data from its smartwatches could be combined with software and services in a medical model Apple could franchise to healthcare systems. Google X started Verily Life Sciences as “a moonshot” aimed at delivering tools and services across the healthcare ecosystem. Verily has a smartwatch designed to help in clinical trials, and tried to develop a glucose-monitoring contact lens. Both Apple and Alphabet subsequently curtailed their direct plays in medicine.

In Apple’s latest health report, Apple Chief Operating Officer Jeff Williams describes the company’s technology as “an intelligent guardian” of people’s health, “so they’re no longer passengers on their own health journey. Instead, we want people to be firmly in the driver’s seat.”

“Google’s products and services are not medical devices providing diagnosis,” said that company’s director of strategic health solutions, Amy McDonough, in a statement, “but they can make a big impact by helping users and healthcare professionals track trends, identify risks and irregularities, and take preventative measures.”

How good are the consumer wearables? When someone is having heart palpitations, smartwatches can detect atrial fibrillation almost as well as gold-standard clinical sensors, according to a review of comparative studies published this year by the Cleveland Clinic. But false alarms are a problem, especially in younger people, where an arrhythmia has a higher chance of being something other than AFib. UnitedHealth Group and Cigna Group pay for monitoring with an iRhythm patch, but not a smartwatch.

Consumer-grade health sensors can funnel people toward healthcare without those wellness devices needing to match the standards of medical devices, says Calum MacRae, a Harvard medical professor who’s leading a project to identify the very earliest stages of heart disease.

Apple Watches and Fitbits have turned out to be the best lead-generators for iRhythm. “A patient comes into a physician’s office saying they think something’s going on…they end up wearing a Zio patch,” says iRhythm CEO Quentin Blackford.

Professional society guidelines still require a gold-standard ECG to make a diagnosis, says iRhythm medical director Turakhia. “You can’t be treated just because a watch said your pulse is irregular. I can’t start an anticoagulant,” he says. Some Medicare Advantage programs screen patients for AFib, he adds, and they use Zio, not smartwatches.

Continuous glucose monitors like DexCom’s have even less to worry about. The smartwatch firms have looked into noninvasive measurement of biomolecules like glucose, but they are unlikely to soon challenge the accuracy of the thread-thin sensor put under the skin by a continuous glucose-monitoring device.

The clinical-grade sensor firms have plenty of growth opportunities in their medical markets, according to William Blair analyst Margaret Kaczor Andrew, who has Buy ratings on iRhythm, DexCom, and Abbott. About 15 million Americans a year come to their doctor with palpitations. Another 12 million may suffer from symptomless AFib. Both DexCom and Abbott recently got FDA approval to market continuous glucose-monitoring devices to the 25 million people with Type 2 diabetes who don’t need insulin. Some 100 million Americans are considered prediabetic.

If Big Tech has eased back its investment in clinical trials of their smart wearables, drug and device companies are carrying on. Johnson & Johnson recruited 26,000 people over the age of 65 to see if early detection of irregular heart rhythms by the Apple Watch can reduce bad outcomes such as stroke; J&J specializes in heart arrhythmia treatments. Ōura supplies smart rings to a bunch of preventive health studies.

IRhythm is sponsoring randomized trials with tens of thousands of subjects in the U.S. and Europe to test whether screening for AFib with the Zio patch can reduce the risk of stroke or heart failure. Earlier studies weren’t decisive enough to convince the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force to add Zio to screening guidelines.

The clinical sensor firms are advancing cautiously into screening and prevention. They saw how the stock of the blood-oxygen sensing firm Masimo was cut in half after the firm spent $1 billion in 2022 on a consumer product business. Facing an activist investor campaign, Masimo recently announced it would unload the consumer business.

“We have to move down the acuity curve,” says DexCom CEO Sayer. “But I don’t think we can just jump to the end of it.”

Write to Bill Alpert at william.alpert@barrons.com

This Barron's article was legally licensed by AdvisorStream.

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.