Sept. 5, 2024

Investors returning from summer holidays might feel dispirited upon checking their portfolios. Stocks have had a poor start to September. America’s S&P 500 index dropped by 2% on its first day of trading. European shares followed suit on September 4th and those in Japan have fallen by even more.

iStock-483785638

It is a striking change from the calm that had settled over markets before Labour Day. American share prices ended August less than a hundredth of a percentage point below an all-time high reached in July, European ones fared similarly and Japanese stocks were just a few percentage points below their peak. Adding to the good vibes, rich-world inflation had continued to cool, setting the scene for the Federal Reserve to begin cutting interest rates when its policymakers next meet on September 17th and 18th.

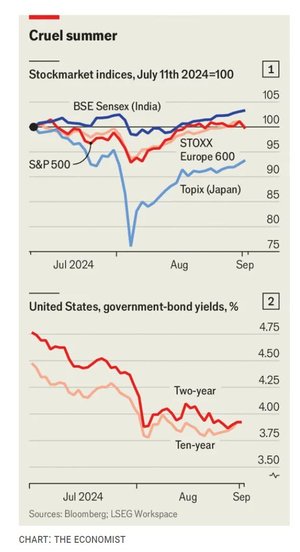

In short, the ructions of early August—when Japan’s Topix index plunged by 20% in three trading days and tech stocks were in a tailspin after a lacklustre earnings season—were an increasingly distant memory. Was it all just a passing squall? The rapid recoveries subsequently staged by most of the major share-price indices would certainly suggest so (see chart 1). But they do not quite tell the whole story. Look beneath them and a fundamental shift has taken place in the make-up of the market. Prior to the turbulence that began to emerge in mid-July, stocks had been on an astonishing run. America’s had risen during 28 out of the previous 37 weeks, their best streak in more than three decades, and plenty of others were also setting records with regularity. Now, and not merely because prices once again started sliding in recent days, the optimism that powered the boom seems to have ebbed away.

First consider the role of America’s big tech firms. The stockmarket’s earlier bull run was led by the strong performance of these giants, which are supposed to benefit from breakthroughs in artificial intelligence. Yet the share prices of the largest such companies have failed to recover as well as the broader market, and those of several have fared far worse. Investors in Alphabet, Amazon, Microsoft and Nvidia are all still nursing double-digit losses following peaks in July. Since these firms make up a large portion of the market, a continued slump would be a significant drag on its overall performance.

In Nvidia’s case this is despite its report, on August 28th, that its second-quarter revenue had more than doubled compared with the previous year’s, to $30bn. Since this announcement, the company’s market value has dropped by 15%. If even such blockbuster performance is no longer sufficient to mollify investors, further gains fuelled by techno-optimism seem unlikely. A report that America’s Department of Justice has sent subpoenas to the firm in preparation for an antitrust probe, which Nvidia denies, does not help.

Meanwhile, government-bond markets are still flashing warning signals. Investors clamoured to buy American Treasuries during the August panic. Yields, which fall as prices rise, duly tumbled (see chart 2). But even as share prices have bounced back, yields have not. For short-term bonds, which track expectations of the Fed’s policy rate, this indicates investors still expect many rate cuts. These would usually be prompted by a weakening economy, suggesting a poor outlook for riskier investments such as shares. Lower yields on long-term Treasuries, meanwhile, show that there is still a clamour to buy some of the world’s safest assets. In other words, plenty of investors fear further storms ahead. And it is not just Treasuries that are being snapped up: yields on British, German and Canadian sovereign debt have fallen. Gold prices are at a record high and are rising fast.

The slightly jarring conclusion is that, even as share prices have returned close to their all-time highs, the extreme exuberance that drove them to such levels in the first place has faded. Investors are no longer in the euphoric mood that characterised the first half of the year.