July 3, 2024

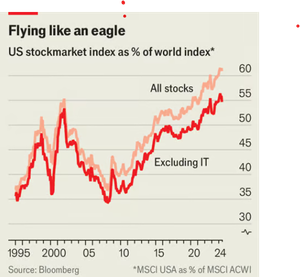

Sixteen years ago American stockmarkets reached their modern nadir. During the early 2000s European and emerging-market equities went on a bull run. By March 2008 America had entered recession and its financial crisis was under way. The country’s stocks accounted for less than 40% of the world’s total stockmarket capitalisation.

iStock-175520590

Fast-forward to today and things look rather different. America’s share of the world’s stockmarket capitalisation has climbed pretty consistently over the past decade and a half, and sharply this year. It now stands at 61%. That is astonishing dominance for a country which accounts for just over a quarter of global gdp. The extent of market concentration is all the more extreme given what is happening within the American stockmarket itself. Just three companies—Apple, Microsoft and Nvidia—make up a tenth of the market value of global stocks.

Chart: The Economist

Investors who would rather not put all their eggs in one basket are worried. Nvidia is now so large that a 13% fall in the chip-designer’s share price between June 18th and 24th, driven by not very much at all, knocked 0.5% off the value of the msci All Country World Index, which covers both emerging and developed markets. The company’s share price later rebounded, rising by 7% over the following two days.

History offers a mixed picture when it comes to market concentration. Sometimes the dominance of a single country or a handful of stocks is a warning. For instance, during the dotcom bubble, which inflated in the late 1990s, the ten largest American stocks made up a third of domestic market capitalisation, similar to their share today. At the country level, Japan provides an ominous example. By the end of 1989, just before its asset bubble burst, Japanese stocks accounted for 40% of the global total. The four largest companies by market capitalisation were Japanese banks.

But concentration can also be benign. During the 1950s and early 1960s, markets were concentrated in both a single country and a small group of firms within it. Europe was still recovering from the second world war and Asian markets had yet to reach global prominence, meaning that American stocks made up as much as 70% of the global market. A handful of blue-chip firms, such as at&t, Exxon and General Motors, were ascendant. Indeed, the ten biggest stocks also accounted for a third of the stockmarket back then, without obvious adverse consequences.

Does today’s situation resemble the benign leadership of the 1960s or the speculative bubble of the late 1990s? Valuations are certainly steep. Nvidia has a price-to-income ratio of 43, based on earnings expected next year. That explains the volatility on show over the past week. Relatively small changes in expectations can drive large movements in market value, especially when a company is as large as Nvidia. The recent broader market rally is based on hopes about the future impact of artificial intelligence, which is inherently uncertain.

Yet even at current prices, there is a gulf between today’s ai-driven optimism and past periods of speculative mania. In 2000 Cisco Systems, a darling of optimistic investors, traded at over 125 times its expected earnings. The price-to-earnings ratio of Japanese stocks—not just the priciest firms, but the entire market—reached 60 in 1989.

Instead of speculative excess, the main reason for America’s dominance is more prosaic. The earnings per share of the msci us index have risen by 162% since March 2008. By contrast, the earnings per share of global markets excluding America have dropped by 2% in dollars terms over that time. More than those anywhere else, American firms have shown an ability to grow, become profitable and return money to investors.

In reality, only a bit of America’s dominance reflects technology companies. Perhaps the most revealing analysis is one that removes them from the calculation entirely. Exclude tech firms and America’s share of global equities falls to 55%. Even that share is the highest it has been in decades, up by more than 20 percentage points from its low in 2008.

This is not an argument for complacency about an undeniably expensive market. But concentration is always a symptom of some driving force. When it comes to America’s current dominance, the driving force is entirely familiar: strong companies in new markets have become highly profitable. Although diversification remains a worthy goal, diversifying away from success is unlikely to leave investors very happy. ■