By Bradley Olson

Jan. 15, 2024

In August, as I prepared to plunge the first syringe of a new weight-loss “wonder drug” into the fatty tissue in my upper thigh, I wondered: What would it feel like to stop being hungry? Since then I’ve lost 40 pounds. This week, I injected the last dose I felt I could afford, and now I’m wondering: What happens when I go back to wanting to eat normally again?

ILLUSTRATION BY DANA SMITH; KIRSTEN GRIND, ISTOCK, GETTY IMAGES (6), ADOBE STOCK PHOTO (2)

Hunger had, in many ways, come to define so much about my life. Most days, I thought often about food, even right after eating. Fifteen years ago, just before I turned 30, I was 100 pounds overweight. I committed to a rigorous diet and exercise program and lost it all in one year, but then like so many in my situation, gradually I gave in to food cravings and began to gain it back again. Around my 44th birthday last year, just months after completing a grueling endurance hike across the Grand Canyon and back, I hit a troubling milestone. I weighed in at 233 pounds, up about 50 pounds from my low. After all those years of trying to maintain my weight loss, eventually I had gained half of it back, and now I had officially crossed the “obese” threshold in body-mass index for the first time in 14 years.

Dieting wasn’t working any more. Now and again, I would try to lay off sugar or carbs, or count calories, or try any number of new ideas to change my relationship with food, but in the end all had failed—or, I thought, my will had failed; I had failed. When I would fall short of my target weight year after year despite hours of weekly exercise, I would think to myself: I am pretty good at a lot of things, and usually, I can accomplish my goals. But not this one. Sometimes, I would lie awake at night and wish that I could find a genie who would make me thin. I knew it was absurd, but such was my state of mind.

The author in 2009 at 280 pounds, just before an earlier campaign to lose weight through diet and exercise. PHOTO: BRADLEY OLSON

While I struggled, along came a new development: a simple weekly injection, a subtle tweak of chemistry that slows the emptying of your stomach and alters the signals that move between the gut and the brain to make you feel full instead of hungry. All of a sudden, what was impossible appeared to become easy—and suggested that the problem wasn’t willpower at all, but underlying biology; that I am not a failure, and never was.

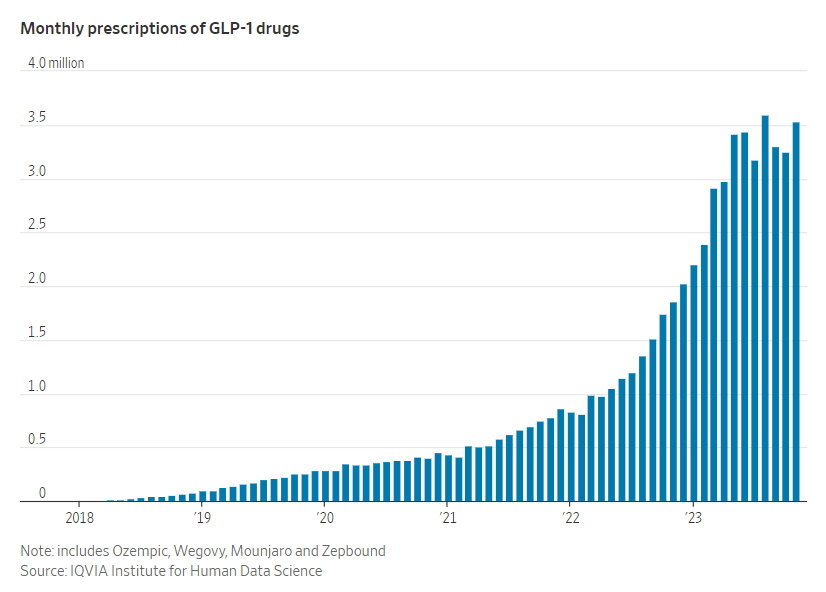

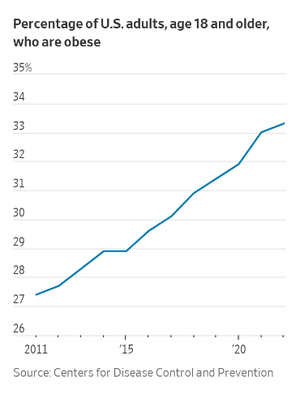

So I made the decision to turn to one of the new so-called GLP-1 drugs. I became part of the biggest medical trend in the country, which has already made billions for Novo Nordisk’s best-known Ozempic and sister drug Wegovy. Some Wall Street analysts expect the newer Mounjaro from Eli Lilly to become one of the bestselling pharmaceuticals of all time, partly because more than two-thirds of American adults are overweight and roughly half of those, or a third of the adult population, are obese. Elon Musk has taken the drugs. Oprah has been taking them, she acknowledged last month. Combined prescriptions of GLP-1s have more than quintupled since 2021, exceeding 36 million in the 12 months ending in November, according to the IQVIA Institute for Human Data Science. Though Ozempic and Mounjaro were developed and authorized specifically to combat diabetes with weight loss as a secondary effect, the use of both as diet drugs has soared as their results have gained notice. Most insurance plans refuse to cover the use of those drugs for weight loss, which has many people struggling to pay the full price themselves—upwards of $1,000 a month (though the companies say discount coupons can lower the cost).

The cost issue applied to me as well. I chose Mounjaro, which has been found to work even better than Ozempic for weight loss in some clinical trials, with patients trimming more than 20 percent of their body weight on average. After discussing the risks with my doctor, I learned that my insurance wouldn’t cover the roughly $1,000-a-month I would need to pay after using a coupon.

Doctors can prescribe these drugs for weight loss in what is called an “off label” use, and my tipping the scales into the ‘’obese” category was enough for my doctor to feel comfortable writing me a prescription. But most patients including me have to pay out of pocket if they don’t have diabetes. (Novo’s Wegovy and Lilly’s newer Zepbound are approved for weight loss, but still many insurers don’t cover them, including mine.)

I was desperate to avoid a long-term slide that would return me again to “morbid” obesity. More and more, I had realized I was fighting biology; my parents and two of my three siblings also have struggled with weight challenges. I decided I could afford to budget the drug for three months, and I hoped it could be the spark I needed to return me back to a longer-term healthy weight—in a way, like the personal training I purchased in 2009 to help spur me to get those 100 pounds off back then. Against my doctor’s recommendation, I planned to spread the three months of doses I could afford over five months instead of three, hoping that would be enough time to firmly establish new eating habits that would help me keep the weight off.

As I gave myself the first jab last summer, my mind danced around so many questions: Would I still enjoy food? Eating, for me, is one of the most reliable and joyful things about life. Often, I have wondered, what do I want more—delicious food that I enjoy but makes me fat, or to be fit? The answer isn’t always clear.

Afraid that my relationship with food might change forever, I even ate what I thought of as a last meal from my favorite Mexican food truck: Three tacos—one with chicken, two with steak.

At first, I felt freed. Shortly after my first dose, it seemed like a chorus of a thousand voices always telling me to eat were finally silent. I wondered, is this what it’s like for skinny people?

The most notable of the vanished cravings were for sugar-laced foods. I noticed right away when I declined a doughnut offer at a school gathering, almost without thinking. A couple of days later, I turned down another. I can scarcely recall a time in my life when I haven’t wanted a doughnut. I had long tried to implement the advice of Michael Pollan, a favorite writer: “Eat food. Not too much. Mostly plants.” But instead, after a few months of South Beach, Keto, Weight Watchers or other popular programs, the reality was more like this: “Eat processed foods. In prodigious volumes. Also doughnuts and chocolate.”

Thankfully, I found that I could still taste and enjoy food, but I could only eat it in small amounts. Many doctors have compared the sensation to what’s experienced by people who’ve had bariatric surgery. Such procedures shrink the stomach’s capacity and slow the passage of food through the stomach. You simply can’t eat very much.

I lost 8 pounds in the first week, a dramatic start and one that came with almost no effort compared with previous weight-loss experiences. I had learned to be skeptical of first-week results, but the declines, though slower, continued. There would be occasional plateaus in the months that followed, but losing weight had never been so easy. It felt like the medicine had leveled the playing field.

About 10 weeks in, I had lost 21 pounds, and I ran into a familiar pattern: Compliments flooded in. At first, I lapped them up, but then they gained a tinge of pain. I couldn’t help but wonder what people thought of me before. If they seemed to be rooting for more weight loss, I would feel a little like I was in an exhibit at the zoo. I had imagined the conversations about my mysterious weight loss would be more fun, since my “success” had nothing to do with will power. After all, there are no motivational speeches on planet Mounjaro. There are no big life lessons about #howtowin. There are simply fewer cravings. It was hard to know how to respond to the kudos.

Most research shows that conventional diets don’t really work long-term. A 2020 analysis in medical journal The BMJ of 121 weight-loss studies involving more than 21,000 people showed that for 14 popular weight-loss programs, modest reductions in the first six months largely disappear at the one-year mark. Only 15% of people who achieve weight-loss of 10% or more of their body weight without surgery or medicine are able to sustain it, according to an analysis of current research published in the journal Nature Metabolism in August.

Yet for most who are overweight, it feels like these are facts that most people, even physicians, don’t absorb. Every weigh-in at the doctor’s office brings familiar advice: eat less, exercise, etc. In what other sphere of medicine do doctors prescribe a cure to everyone with a common illness that works only 15% of the time? The legacy of all of that failed effort, juxtaposed with the easy success of the medicine, comes with a lot of cognitive dissonance. When you have fought for something your whole life, only to fail regularly, finding a quick and easy solution is jarring. It can make all the messages you internalized—from doctors, friends, advertisers, influencers and others beyond counting—seem like a big lie.

With this recognition, anger began to rise inside of me like a storm, first at the diet-industrial complex, the multibillion-dollar apparatus that has failed so many fat people, all while bringing a sizable portion of shame and self-loathing. Then, my frustrations turned to the American diet, where sugar is almost unavoidable. And lastly, as I prepared to purchase my third and final set of four weekly doses, my thoughts turned to the pharmaceutical industry, whose solution for people of my size is essentially a life sentence of paying as much as $12,000 a year.

Before I started taking the medicine, my doctor, Alph Wise—a friend whose bodily proportions and enjoyment of the outdoors are similar to mine—had warned me about the fundamental problem with the new weight-loss drugs. Early clinical tests had shown that the vast majority of those who stop taking the medicine gain most of the weight back, much like in the aftermath of diets. After I began my treatment, that evidence only mounted. A clinical trial of 670 people published in December showed that patients taking the active molecule in Mounjaro, who initially lost 21% of their body weight in about nine months, gained most of it back after another year. Only about 17% of those who stopped taking the drug kept the weight off, roughly the same failure rate of most nonsurgical, non-pharmaceutical weight-loss solutions.

I knew the risk of relapse when I took it, but I hoped that focusing on renewing my healthy habits at the same time would help me find a new equilibrium with food by the time I ran out of doses.

Meanwhile, my initial success gave me so much confidence that I wavered about whether to pay for the final round of medicine that I had planned. While initially I enjoyed the drug’s ability to hack my brain and mute my hunger signals, I had grown uncomfortable with some aspects of taking it. On certain days, it had an impact on my ability to enjoy food. The sensation reminded me of having a mild case of acid reflux. The thought of eating was generally unappealing, even if I hadn’t eaten much; though I didn’t experience nausea, others on GLP-1 drugs have. At times, hunger would briefly break through before dinner, but if I were to nosh on a handful of peanuts—not normally a dinner-ruining snack—I wouldn’t be able to eat much more than a bite or two. I had traded one kind of food anxiety for another: I had to learn to eat just the right amount, at just the right time. I came to yearn, as I had feared, for the experience of being satisfied by food.

Knowing that going off the drug was inevitable, I wondered whether I should just rip off the Band-Aid and be finished with it. Then, I put on an old “new” shirt.

Five years ago, my wife bought me a plaid, button-up shirt with vaguely Western tones that I absolutely loved. The fit was unfortunately much too tight, but I kept it, reasoning that I would soon slim down enough to wear it. It had never come close to fitting, but I kept it, a talisman of either hope or despair.

I decided to try it on. It fit like a dream.

Losing a lot of weight is like meeting another version of yourself. Hollywood has inundated all of us lately with the “multiverse,” a concept that imagines the possibility of parallel universes. In some multiverses, I am probably thin, right? Maybe I even have six-pack abs? Such musings are reminiscent of Kafka’s “Metamorphosis” but in reverse: instead of becoming an insect, you transform into a beautiful person that everyone apparently loves. Of course, all the while, you are thinking, I am the same person, I haven’t changed. And then, you start to learn that there is an unusual relationship between what people perceive in us and who it can lead us to become.

So, wearing what turns out to have become a very important shirt, I bought the final dosage and proceeded to tear through the holidays, dropping below 200 pounds during the normally daunting sequence of Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s Eve. In previous diets, this five-week sequence has often been a diet killer for me (and many others). A group leader at a Weight Watchers meeting I attended more than 20 years ago described Thanksgiving this way: “It’s David versus Goliath, and Goliath is Thanksgiving.”

My Goliath is dead. Mounjaro killed him.

I made no New Year’s resolutions. I knew I didn’t need them.

This week, as I took my final injection, I couldn’t help but wonder at the change I’ve seen. Physically, my face is chiseled and square. My wedding ring nearly slips off. Pants that I bought two months ago are baggy. I am on the last rung of my favorite belt. My waist has gone from 40 to 38, and 38 to 36, and now I’m approaching 34.

Mentally, the change feels even greater. After years of longing, I had labored to reach a point of acceptance about my weight. “This is just how I am,” I would say to myself. “My beach body is whatever body I happen to have when I choose to go to the beach.” These are the thoughts that are required to hold back obsession and body toxicity in a world where lasting weight loss has been impossible for many.

What if it isn’t impossible anymore? I expect the drugs will one day be as widespread and affordable as statins, prescribed to reduce cholesterol and high blood pressure—no willpower required.

As the final syringe went into my thigh, I reflected on all my past weight-loss experiences. Whether it’s diet, or exercise, or any number of plans and routines, they only work—even temporarily—if you believe. Your mind has to be a lockbox or you won’t last a week. So, I have tried to pour cement around the idea that the dam will hold. I have been working out ferociously and eating like I’m in a healthy-dieting competition. Michael Pollan would be proud.

I know the odds, but I choose to believe. Sometimes, it’s all we have.

During the course of taking Mounjaro, I have thought often about “Awakenings,” the book and movie about the experiences of neurologist Oliver Sacks. Sacks chronicled how the use of a new drug, L-dopa, helped catatonic patients “wake up” after years of living in a statue-like condition. Yet for many, the book relates, the success in treatment was temporary.

There are echoes of that story in this medicine, too. For me and millions of others, it is working, and people have what they think is a new lease on life. Although the evidence of rapid weight regain has led many clinicians to believe the best course is staying on the medicine permanently, that may not be sustainable. In the past few months, it has been difficult at times for me to eat more than 1,000 calories in a day. If one is already thin or exercises heavily, it seems excessive to keep using an appetite inhibitor along with its side effects, especially considering the current cost, so going off the drug seems inevitable.

There isn’t yet extensive research on whether these drugs could be combined in some kind of balance with the many dieting and exercise programs that haven’t been proven to work in a lasting way by themselves. That’s the frontier I am now entering, along with many others. Here’s hoping for us all.

Bradley Olson is a technology editor in the Journal’s San Francisco bureau.

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.