By Karen Langley

July 22, 2024

The stock market has suddenly turned upside down.

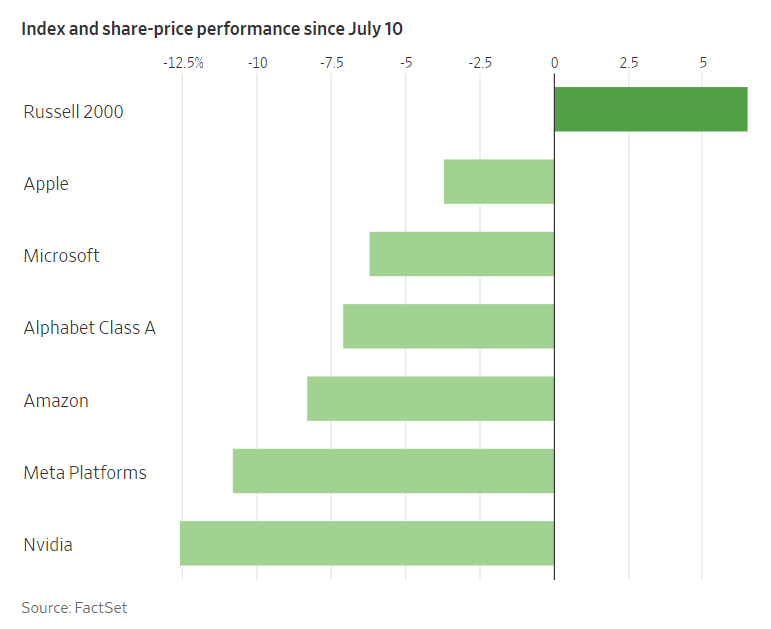

The market’s laggards have sprung to life in recent days, while the seemingly impervious “Magnificent Seven” group of technology stocks has stumbled.

Investors are even more focused than usual on corporate earnings as they try to anticipate what comes next.

As the Fed continued to raise rates and then kept them high, investors rushed to megacompanies that they bet could withstand economic uncertainty. PHOTO: TING SHEN/BLOOMBERG NEWS

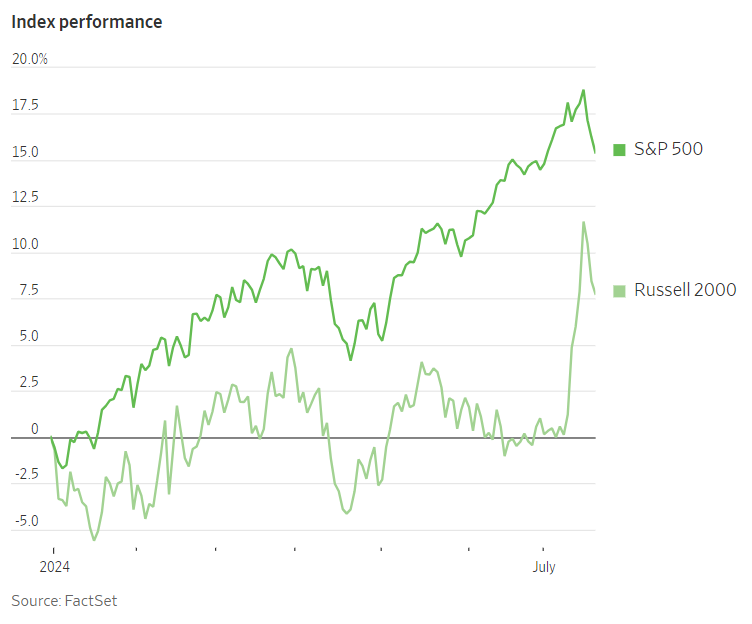

The Russell 2000 index of smaller stocks beat the S&P 500 over the seven days through Wednesday by the largest margin during a period of that length in data going back to 1986, according to Dow Jones Market Data. The Russell 1000 Value index, meanwhile, notched its biggest lead over its growth-stock counterpart since April 2001, after the dot-com bubble burst.

Few investors saw the shift coming, and many are puzzled by what is behind it: Changing forecasts for Federal Reserve interest-rate cuts? Expectations that Donald Trump will return to the White House? A technology trade that grew precariously crowded?

President Biden’s announcement Sunday that he wouldn’t seek re-election augmented the uncertainty and promised to refocus market attention on the presidential campaign.

Now, investors are scrambling to determine whether the reordering of winners and losers is a mere blip in an era of tech ascendancy—or if a sustainable shift is in fact under way.

“That’s what everybody is trying to answer,” said Raheel Siddiqui, senior investment strategist at Neuberger Berman.

The small-cap index rose 1.7% this past week, extending its 2024 advance to 7.8%, while the S&P 500 dropped 2%, trimming its gains to 15%.

As the Fed continued raising rates to tame inflation in 2023 and kept them elevated so far this year, investors rushed for the safety of mega-size companies that they bet could withstand economic uncertainty. Some of those same companies were primed to capitalize on potentially transformative advances in artificial intelligence.

Traders looked askance, meanwhile, at shares of smaller and more cyclical companies that tend to be particularly vulnerable to higher financing costs and to the risk that the central bank’s rate increases would tip the economy into recession.

The trade seemed unstoppable. Then on July 11, a surprisingly cool inflation report appeared to change everything. While investors had long expected the Fed to begin trimming rates, the data made them nearly sure that those rate cuts would begin in September. Believing the shift toward lower rates was almost upon them, investors raced to trim their winning bets on tech and lean into parts of the market likely to rally when rate cuts lower borrowing costs and boost the economy.

“Who benefits as rates come down? The answer is the ones who suffered the most when rates went up, and it’s basically the weaker players,” Siddiqui said.

When the Fed began its rate-increase campaign in March 2022, the yield on the benchmark 10-year U.S. Treasury note, which influences borrowing costs throughout the economy, was around 2.2%. Over the following months, the Fed raised rates and the yield climbed. In October 2023, it topped 5% for the first time in 16 years. Yields then fell as investors began to anticipate rate cuts but have risen in 2024 as inflation remained stubbornly persistent. The 10-year’s yield ended Friday at 4.238%.

Another force at work in markets: growing expectations that Trump will return to the White House after the November election, potentially increasing the odds of tax cuts and lighter regulation.

For the rotation of market leadership to persist, many believe that results and forecasts from individual companies will need to reinforce the view that smaller and more cyclical businesses are poised to perform.

Investors will look for clues this week in the quarterly reports of Google parent Alphabet and electric-vehicle maker Tesla, along with nearly 300 companies in the small-cap Russell 2000. The following week will bring additional insights into Big Tech when Microsoft, Meta Platforms, Apple and Amazon.com share results.

It isn’t just excitement that has driven the tech trade. The companies enjoy dominant positions in huge markets and operate at a scale that gives some insulation from economic fluctuations.

Together, the Magnificent Seven—Alphabet, Amazon, Apple, Meta Platforms, Microsoft, Nvidia and Tesla—reported a 52% increase in profits for the first quarter of this year, compared with a decline of 8.7% by the remaining 493 companies in the S&P 500, according to Ryan Grabinski, investment strategist at Strategas. Analysts expect the septet to report a 28% jump in earnings for the second quarter, while profits from the other S&P 500 stocks slip 1%.

Russell 2000 companies, meanwhile, are expected to report a nearly 18% rise in second-quarter profits, snapping a five-quarter streak of year-over-year declines, according to LSEG I/B/E/S data. Among the small-cap companies reporting this week are egg producer Cal-Maine Foods and printer maker Xerox.

“Earnings growth is going to be a crucial factor in determining whether this trend will continue—earnings growth of smaller names and earnings growth of the large-cap tech companies,” said Sumali Sanyal, senior portfolio manager of systematic global equities at Xponance.

Smaller companies tend to be more vulnerable than big ones to high interest rates. Thirty percent of the debt of the Russell 2000 is floating-rate, compared with 6% for the S&P 500, according to Goldman Sachs research from earlier this year. Historically, unprofitable companies make up a large chunk of the Russell 2000.

Those factors contributed to investors’ lack of enthusiasm for the group as the Fed kept rates high: The Russell 2000 inched up just 1% in the first six months of the year.

The biggest stocks drove the S&P 500’s rally. In the first half of the year, just one company—chip maker Nvidia, a darling of the AI trade—contributed 30% of the S&P 500’s 15% total return, including dividends, according to S&P Dow Jones Indices. Add in Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms, Alphabet and Apple, and you have accounted for well over half of the index’s return.

The small number of stocks powering the S&P 500 has worried investors, making them question the sustainability of the rally.

“That’s really risky, and it’s nice to see this broadening,” said Nancy Curtin, chief investment officer at AlTi Tiedemann Global. “That creates a healthier market, a more stable market, and gives more legs to the bull market, frankly.”

Write to Karen Langley at karen.langley@wsj.com

Dow Jones & Company, Inc.